2003-11-01李瑞Source:

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This paper reviews major points related to China's efforts for sustainable industrialization and a well-off society, the theme of the 2003 CCICED Annual General Meeting. The purpose is to provide background on both international and Chinese experience and to set the stage for discussion and development of recommendations by the Council. The paper complements the reports of five Task Forces being presented to CCICED this year, each on a particular area related to sustainable industrialization. The link to xiaokang, an "all-round, well-off society", places emphasis on equity and various concerns related to quality of life, using the wealth creation, knowledge and products created by industrial development.

Sustainable Industrialization

Sustainable industrialization is a process of development that (1) sets and meets wealth generation and production objectives that support Chinese and, when appropriate, international sustainable development goals; (2) builds capacity and sets conditions for enterprises of all sizes to meet "triple bottom line" financial, social and environmental objectives; and (3) provides for institutional reform and commitment to innovation in order to meet these objectives. It depends upon the interplay of government and business, community, and other interests, including those of international organizations to set objectives, guidelines, regulations and incentives. New metrics will be needed in order to adequately understand and communicate progress on achieving both sustainable industrialization and its link to a well-off society.

China is drawing upon globally-recognized concepts such as eco-efficiency, polluter pays, Cleaner Production, Eco-industrial parks, as well as some that are more specific to various countries, such as the idea of the Circular Economy. These ideas, while very important, provide only part of the picture of an emerging new approach. Sustainable industrialization depends very much on overall structural reform of industry, regulation based on a broader array of instruments and voluntary measures, and both fiscal and financial reform.

As individual sectors and enterprises move along their "Sustainability Journey" the role of innovation becomes important in order to develop new material and energy-efficient industrial processes and environmentally and socially sustainable products. China is encouraging investment in new sectors such as environmental technology, alternative energy, information technology, biotechnology and nanotechnology that should help achieve advanced objectives, including those involving a commitment to technology leapfrogging.

Urban planning and development, government procurement policies, and the tremendous need for new installed capacity of various industrial infrastructure offer many very significant opportunities for making choices in favour of sustainable industrialization. Balanced against these largely positive elements are some major difficulties, for example, the uneven performance of provinces in enforcement of environmental regulations, the issues of old industry including some obsolete state enterprises, the technical and financial difficulties of the very economically important small and medium-size enterprises, and extensive policy and institutional reform needs. China also faces international competitive pressures, trade and environmental negotiations, and growing expectations internationally for improvement of corporate social responsibility, and higher environmental and social performance levels.

Chinese Data Trends

This section of the paper, to be completed for the CCICED AGM will provide additional information that illustrates areas of progress and also some dilemmas.

Ten Issues for Discussion

The purpose of this paper is not to identify specific recommendations. But a number of issues and questions arise. The ten themes summarized below are a starting point for general discussion on how to improve China's sustainable industrialization efforts, and strengthen the linkage to a well-off society. They are discussed in somewhat more detail in Section III of the paper.

1. The link between sustainable industrialization and a well-off (xiaokang) society goes beyond issues of wealth creation and distribution, and these broader dimensions need considerable attention. How much and how broadly should sustainable industrialization be expected to contribute to a well-off society in China? Can this be done in a way that actually improves the profitability and right to operate of individual enterprises, while also reducing rather than contributing to China's overall environmental debt?

2. The success of sustainable industrialization will depend upon how well other components of sustainable development are implemented within China. How can intersectoral communication and cooperation on sustainable development be enhanced so that the full potential of sustainable industrialization is realized, including its contribution to other processes such as sustainable urbanization?

3. Fiscal reform and financial sector reform are necessary to achieve sustainable industrialization. Given a need for both fiscal reform and financial sector reform in order to achieve general development goals within China, which reforms are most likely to be useful in achieving sustainable industrialization, while at the same time contributing to a well-off society?

4. The appropriate scale for individual enterprise development and its relationship to both sustainable industrialization and urbanization require policy attention. Should China restructure its industrial base to encourage development of larger-scale industry that may be more capable of addressing sustainable industrialization? And, if so, are there strategic sectors to start this process, and sectors where it is still particularly important to foster SMEs?

5. The legal framework for sustainable industrialization is still incomplete, but there are real tradeoffs between adding new laws and enforcing existing laws and regulations. Are there critical gaps in legislation and regulations to support sustainable industrialization, and if so, what should be the appropriate balance between adding new rules and improving enforcement of existing ones? How can enforcement be made more consistent at provincial and municipal levels? As well, more attention needs to be given to incentive-based approaches to industrial regulation. What are the most important areas to address using this approach?

6. China is not achieving an optimal transfer of environment and sustainability technology from abroad, and the rate of technology leapfrogging is less than would be desirable. There is a need to speed up the development of a Chinese environmental protection and sustainable development industrial sector. How can environmental protection and sustainable technology sector development be accelerated so that it can adequately support the needs of sustainable industrialization? And can the sector be developed in a fashion that stimulates innovation within industry, leading to useful, environmentally sound products that will contribute to a well-off society?

7. Measures of progress for sustainable industrialization in China are weak, and even less well developed for the linkage between this new style of industrialization and a well-off society. How can sustainable industrialization progress be monitored and measured in relation to its own performance and for its contribution to a well-off society? Which sustainability indicators are likely to be most useful, and can they utilize existing statistical information?

8. Capacity-building is highlighted by many sources as a high priority need within virtually all segments of the industrial sector, in regulatory systems at national and local levels, within the management structure and board room of individual enterprises, and in financial institutions. The gap between skills required for sustainable industrialization and their supply is already large, and likely to increase over time unless there is concerted action and considerable foresight. What are the most critical actions that can be taken during the existing and coming Five Year Plans, and within the private sector to address the gap?

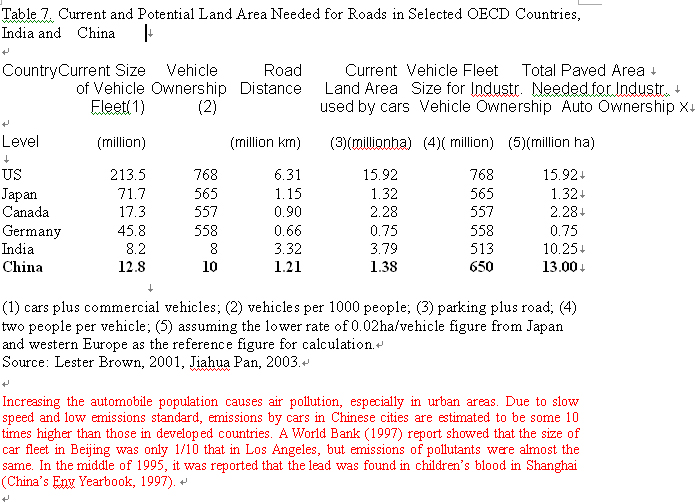

9. China's domestic market potential attracts attention from those who ask the question of whether the world's ecosystems can support Chinese consumption at levels anywhere near those of western society; and others who see this emerging market as the most significant place in the world to stimulate consumption and, therefore, demand for their product, whether or not the product truly improves well-being or sustainability. What actions are needed within China's domestic marketplace to develop and reinforce sustainable consumption patterns, and how might such efforts improve both sustainable industrialization and the achievement of a well-off society?

10. Chinese efforts for achieving sustainable industrialization and a well-off society are taking place at a time of evolving international views towards globalization and development. Almost certainly there will be surprises (e.g. SARS) leading to international responses that may threaten progress. How can China reduce its vulnerability to potentially damaging events and perceptions that may affect its international markets, sustainable industrialization progress, and capacity to be fully engaged in a globalized world?

Conclusion

China's best efforts could be derailed by a convergence of problems, with only some directly controlled from within the country. Therefore it is important for the international community to support the Chinese sustainable development effort in various ways, even where there may be issues of industrial competition. Within China it will be more and more important to build dialogue, partnership and action across major sectors, for sustainable development demands this type of exchange.

No one yet knows how different China's approach will be compared to international norms, and to industrial development in other countries that developed along lines now considered to be unsustainable.

China has surprised the world with its rapid and dedicated efforts for economic development. With this same degree of dedication directed towards sustainable industrialization and xiaokang, we can hope for an interesting and globally significant business and sustainable development transition.

SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIALIZATION IN CHINA

AND A WELL-OFF SOCIETY

Discussion Paper

Prepared for the Annual General Meeting of CCICED

30 October – 1 November, 2003

I. SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIALIZATION AND A WELL-OFF SOCIETY

PURPOSE

China faces massive challenges and major opportunities during the decade ahead—when the nation makes a transition to becoming one of the leading industrial producers in the world, operating within the rules of the World Trade Organization. Through a series of policy statements and bold action, China has signaled its intent to use this export-driven industrialization process as a key means to achieve sustainable development. The industrialization effort is intended to take into account the need for distribution of economic and social opportunities throughout the country. The outcome should be the achievement of a xiaokang society, i.e. a well-off society built in an all-round way that pays attention to progress in five dimensions—economic development, material life, population quality, cultural life and environment. These views were reinforced at meetings of the National People's Congress and the Political Consultative Conference held in March 2003.

This discussion paper is intended to focus attention on pathways that might be considered in order to achieve these dual objectives of sustainable industrialization and a well-off society, and some of the barriers that may have to be overcome. It explores relevant international and Chinese experience, and provides recommendations for discussion at the CCICED Annual General Meeting 30 October - 1 November 2003.

DEFINING SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIALIZATION

While much has been written on the subject of business and sustainable development , and on individual "sustainable enterprises" , sustainable industrialization as an overall process contributing to a country's sustainable development is less well understood, although there are a variety of views. A reasonable definition of sustainable industrialization should take into account transformation in the structure of industrialization, including scale, the ways enterprises use natural resources and human resources, the role industry can play in fostering sustainable urbanization and livelihoods, and other key linkages of industry with society.

In China's Tenth Five Year Plan, structural adjustment of industry is addressed as a key theme. More than a dozen industries are given priority attention in this adjustment, including: machinery, automobile, metallurgy, nonferrous metal industry, petroleum, petrochemical, chemical industry, medicine, coal mining, building materials, light industry textiles, electric power and gold. This eclectic list demonstrates a considerable focus on heavy industries, often considered as among the "dirty industries" of the past in OECD nations. The list of "industries, products and technologies currently encouraged by the State" as of 2000 included some 28 areas of industry, with over 526 products, technologies and services. There is a strong interest in developing high technology approaches, with a major emphasis on information technologies.

Structural adjustment of Chinese industrialization involves several policies :

• Supporting and upgrading industries, products and enterprises that can improve China's competitive power through capital investment, bond issues, debt swaps, etc.

• Encouraging the reform of traditional and strategic industries through tax reduction and remittance.

• Creating a competitive environment for business through: a fair investment tax policy, strict technology and quality standards, anti-monopoly laws and regulations, and rapid market information services. Importantly, not all industries are covered, for example, those related to national security, "natural monopoly", and new "high-tech" industries.

• Restrictive industry policy designed to eliminate industries where supply exceeds demand and where there may be a low technical content and/or major environmental pollution.

• Protective policies to cover agricultural, service and "young" industries considered vulnerable to international competition. Such policies need to take into account China's accession to WTO.

These structural changes are reinforced by several mechanisms, including preferential loans and fund-raising via banks such as the China Import and Export Bank, the State Development Bank and the China Agricultural Development Bank.

As well, decisions about industrial development are informed by several principles, including conformity with the national sustainable development strategy, contributing to energy efficiency and improving ecological conditions. Another set is related to technological advancement, including expanding domestic technology contributions to industrialization, with new opportunities for economic growth. A third is to address domestic market needs and to contribute to fast, sound development of the national economy. All of these concepts, of course, could contribute to sustainable industrialization.

The above paragraphs have introduced China's efforts to modernize industry, and how such efforts can be related to sustainability and a well-off society. When we examine the pattern of China's industrialization in more depth, it is clear that the challenges of sustainability will indeed be great. No other country has embarked upon transformation at such a scale, and at a time when so many options for the future are available. China's industrialization is taking place in a period when many OECD nations are engaged in, or entering a post-industrial phase, with a current emphasis on an information economy. And, beyond that, there are new directions emerging in these richer nations, for example, the new biological economy, based on many advances, for example, in genomics, new industrial enzymes and ecological services such as carbon sequestration. Thus China's policies towards industrialization must be extraordinarily sensitive to new opportunities beyond the heavy industries and manufacturing typically profiled within industrial strategies.

To conclude, sustainable industrialization for China might be defined as noted in the box.

SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIALIZATION IN CHINA

A process of industrial development that (1) sets and meets wealth generation and production objectives that support Chinese and, when appropriate, international sustainable development goals; (2) builds capacity and sets conditions for enterprises of all sizes to meet "triple bottom line" financial, social and environmental objectives; and (3) provides for institutional reform and commitment to innovation in order to meet these objectives.

XIAOKANG—AN "ALL-ROUND, WELL-OFF SOCIETY"

Xiaokang, an ancient concept for a social ideal within China , has been solidly endorsed in recent months. In past years it was applied as Deng Xiaoping's vision of modernization in China at the time opening to markets began. It was envisioned as a process where first subsistence, then higher levels of wealth were to be created—a quadrupling of GDP between 1980 and 2000 to achieve a basic xiaokang society. The further modernization process was to be until 2050, at which time Chinese per capita income levels would reach those of mid-income countries. By 2000 the term "well-off" covered a considerable range, from survival to affluence. The target set by Jiang Zemin was to further quadruple GDP between 2000 and 2020. However, a measure such as GDP says nothing about equity, and that is the concern being addressed by the use of the term "all-round, well-off society."

The 30 million or more Chinese living more or less in absolute poverty, without access to sufficient food and clothing, fall far below a stage of xiaokang. And as expectations continue to rise, perhaps the term itself will be redefined from the modest levels originally envisioned. Will it mean an automobile for most households? Travel abroad at regular intervals? The line between well-being and affluence in China may well blur, just as has happened in many other societies. And income alone is not the only consideration. Well-being also needs to be defined by factors such as living conditions that promote good health, access to education and training, good standards of accommodation, amenities for recreation, the means to be creative, and a good quality of environment. Fairness, transparency and consistency in addressing citizen needs and concerns is important element for societal and individual well-being. Social security is a major concern. Thus, citizens should enjoy "well-off lives in the broadest of senses, not only materially, but socially." All-round xiaokang is to be met by 2020 according to current strategy.

Xiaokang is important in the regional distribution of benefits of development, including those derived from sustainable industrialization. In particular Western Development, central region development and re-development strategies in parts of northern China will demand special attention. Reduction in the agricultural workforce from 50% to 30% over the first two decades of the 21st Century focuses attention on both industrialization and urbanization policies and priorities, since both livelihoods and location of where people live will be affected.

Employment strategy is, of course, essential to xiaokang. Of paramount importance is the creation of job opportunities for those being displaced from agriculture (about 1.7 million per year). The role of sustainable industrialization is important, but not necessarily the most critical component of job creation. The World Bank estimates that between 1990 and 2002 China generated many more jobs in the service sector (7.6 million jobs annually) compared to 1.6 million annually within industry. These figures do not tell the whole story, of course, since the quality of future jobs will depend upon technology choices that are yet to be made, and many service jobs are dependent upon wealth generation from export-oriented industrial production.

Hu Angang (see footnote 7), Director of the Center for China Study at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, indicates that reality today is "one China, four worlds": 2.2% in cities such as Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing with a "high-economy"; 21.8% in coastal regions such as Guandong, Zhejiiang, Jiangsu, and Liaoning with "upper-middle economy"; 26% in Hebei, Jilin, Heilongjiang, and parts of central China with a "lower-middle economy"; and 50% in central and western China living under "fourth world" economic conditions, paralleling the poorest regions of the world. This view is oversimplified. Nevertheless, it dramatically conveys the magnitude of the challenges ahead for achieving xiaokang.

The World Bank's multiple capitals approach seems particularly relevant to this discussion. Overall, there is a need to consider both social and human capital plus the built capital of infrastructure and natural capital. And the strategy of sustainable industrialization is important for providing the future financial capital needed for xiaokang.

Finally, while equity is a key consideration in the new strategy for "getting rich together", it is also clear that it is not necessarily at the expense of greater efficiency in the industrialization process. At least that would appear to be the case. Thus, efforts in China will intensify to reduce support for obsolete industrial firms, and for at least some of the state-owned enterprises that are not capable of operating efficiently. Much of the future investment will be in high-technology industries that may not employ as many people but will produce much more output with lower levels of energy and material flow-through.

Sustainable development relies in large part upon the outcomes arising from macroeconomic policies, and other national-level policies that shape the relationship between industrialization, urbanization and other factors such as agricultural land use and social services. There appears to be no existing framework within China that defines the relationship between sustainable development and xiaokang. This is an important priority. Are they one and the same? What differentiates them? How do they reinforce each other? And can they be adequately measured? China's Agenda 21 probably comes closest to providing a framework. But it is very comprehensive and complex, and subject to many interpretations.

One interesting effort to provide a social and ecological accounting matrix (SEAM) for China has been provided by Xiaoming Pan from the Institute of Systems Science in the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It is an attempt to build a simpler accounting system than that proposed by the UN Commission on Sustainable Development. Still, some 60 indicators are involved. Pan has produced a useful summary table with information on some 30 indicators divided into five categories: DEMOGRAPHIC, e.g. net growth rate; ratio of urban residents; ECONOMIC, e.g. GDP per capita, inflation rate, ratio of foreign investment, ratio of tertiary industry, ratio of R&D to GDP; SOCIAL, unemployment, social security coverage; RESOURCE, cropland per capita, energy intensity; ENVIRONMENT, water pollution index, air pollution index; EDP reduction (estimated net loss of natural resources and environmental assets).

Pan concludes with the good news that industrialization has proceeded to the point where less ecologically intensive tertiary industry is now over 30% of all industry, and that the trend towards urbanization should help with implementation of family planning. However, Pan notes that major sustainability obstacles exist: low ratio of R&D expenditure, unemployment arising from the transition to a market system, limited coverage of the social security system, shortage of cropland, relatively low energy efficiency, and worsening pollution arising from rapid industrialization and urbanization. And, the Ecological Domestic Product (EDP) calculations suggest that China's GDP should be reduced by about 3.4% when the net losses of natural resources and environmental assets are considered.

The 10th Five Year Plan provides the short-term guidance that will help move Chinese society towards sustainable development, including sustainable industrialization and xiaokang. Longer term guidance is provided by the 20 Year Plan discussed in the Party Congress.

ENTERPRISES, SUSTAINABILITY AND SOCIETY

The Sustainability Journey

Two decades ago, environmental action on the part of industry focused mainly upon compliance to prescriptive laws and regulations, generally based upon point source pollution control, best available technology and zoning. This was true for OECD nations as well as for developing nations. Many were still in the early stages of creating national legislation and environment units within government departments. The strengths and shortcomings of this approach became clear, along with the realization that compliance alone falls short of sustainability.

Risk assessment, often driven by concerns over right to operate and corporate liability, became commonplace by the mid-1980s. Driven by insurers' concerns over toxic wastes, bankers' concerns about providing loans for firms and properties with environmental problems, and the realization that "pollution prevention pays", industrial sectors and individual enterprises engaged in more proactive, often voluntary, action. A very successful example is the Responsible Care Program of the chemical production industry in North America and Europe. This program dramatically reduced the production of many toxic wastes by fundamental changes in manufacturing methods, rather than relying mainly upon end-of-pipe pollution control. Since then, Responsible Care has been implemented in other sectors throughout the world. Yet sustainable industrialization could not be achieved through addressing risk and compliance.

A missing element gradually emerged during the 1990s when leading businesses, especially some multinational corporations, redefined their performance around a "triple bottom line" through practices that are good for the environment, for people, and for the financial performance of the firm. Instead of a net cost to business, addressing environment and development concerns in industry could be seen as a means of enhancing the profitability and, ultimately, the shareholder value of the firm. The triple bottom line is today's best effort to create a definition of sustainable industry that works for both business and society.

Much of the impetus for this approach came from the corporate members of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), which also pioneered the

concept of eco-efficiency as well as more comprehensive reviews of particular industrial sectors such as pulp and paper and mining; UNEP's Cleaner Production initiative; from management consultants such as Sustainability; and from visionary individuals and organizations (e.g. Karl Heinrich, The Natural Step; Amory Lovin, The Rocky Mountain Institute).

The common thread from these and other sources of inspiration for sustainable industrial development is a focus on innovation—to produce products fulfilling genuine need; to create 100% product via byproduct synergy and elimination of manufacturing methods that produce pollutants; to reduce by ten-fold the amount of energy and material flow-through of industrial products and processes ("Factor 10 Club"); and to create a circular economy with a "cradle to grave" stewardship approach during a product's life cycle.

This transition of thinking and action is often referred to as the "Sustainability Journey". The idea of a journey is that on-going opportunities for improvement exist, objectives can be re-defined, and new pathways to sustainability can emerge. It is certainly not a journey for industry alone. Governments play a vital role: through the signals sent in terms of expenditure, tax and subsidy policies; through the mix of economic and command-and-control environmental and other regulations; and through planning decisions, especially at local levels where zoning, land and water restoration and controls over watersheds, groundwater and airsheds are critical elements. Civil society institutions throughout the world also play an important role through their influence on consumers, on international negotiations in both trade and environmental agreements, and on performance monitoring. Still, few would argue that any final destination on the Sustainability Journey has been reached—in any country, or for any industry. Indeed, the goals of industrial sustainability can be continuously refined, and new opportunities to address these goals arise with new knowledge and experience.

Individual enterprises around the world and in China are found at all stages of their Sustainability Journey. Unfortunately many do not even come close to the most basic levels of compliance. In theory, and often in actual practice, such firms, whether SMEs, large state-run enterprises, or some MNCs, are highly vulnerable—lacking in domestic or international competitiveness, and perhaps unable to raise money for needed improvements. Their liabilities, however, may be left for the broader society to cover, often in the form of increased health problems arising from pollution, expensive restoration of urban brownfield sites, or option foreclosure including loss of new livelihood opportunities. A key concern, therefore, is how to simultaneously improve the sustainability performance within entire sectors, including the full range of individual enterprises, large and small.

Certainly sustainable industrialization must be considered in the context of the broader directions of sustainable development of a nation. This is particularly important for China, given the country's efforts to develop a socialist market economy that will lead to moderate affluence for most people. This will require an on-going commitment to very high levels of economic growth. Can these levels be maintained while substantially improving the environment rather than causing further harm? Tough decisions will be needed in order to focus investment in industrial pathways that champion innovation. Considerable progress has been made, but the steps are small compared with what lies ahead. Indeed, most of China's investment on sustainable industrialization is yet to come.

In the world of the 21st Century, expectations in the countries where China markets many of its products are that ever-greater levels of corporate social responsibility should form an important part of sustainable industrialization. There are international expectations about levels of transparency and openness on the part of both government and industry that are beyond those found at present on the part of most Asia-based enterprises.

These are issues that will have to be faced by China, especially now that it is subject to the rules of the WTO, and to those of international environmental agreements, and to non-compulsory but important tools such as green certification and eco-labeling. Trade and sustainable development are subjects that are now interlocked in ways hardly conceivable a decade ago.

Cleaner Production (CP) – A Cornerstone of Chinese Environmental Action

Internationally, through the efforts of UNEP, the concept of Cleaner Production is becoming a mainstream effort to make the transition from conventional pollution control methods. It is an approach that has become a cornerstone for China's efforts, now that the country's Cleaner Production Promotion Law is in force (as of January 2003.) Cleaner production depends upon continuous innovation that should lead to:

• Processes and production systems that are more profitable and less wasteful of materials and energy; and with less dependence upon non-renewable resources.

• Products that will have better performance and durability, are less toxic, more durable, and recyclable or biodegradable, with lower greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants.

Cleaner Production should convert thinking away from waste disposal and towards 100% product from industrial processes.

While CP is certainly important for achieving sustainable industrialization, the terms are not synonymous. As noted by OECD , "Sustainable means clean enough to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Making the distinction between 'cleaner' and 'sustainable' requires the tools to assess and compare the performance of different technologies used for industrial production." In general, today's Cleaner Production approaches fall short of the qualitatively different types of sustainable industrialization called for by the Factor 10 Club , proponents of Biomimicry , The Natural Step , and other leading edge initiatives.

What Cleaner Production can do is reach out to the vast majority of businesses that are still at early stages of environmental strategies and provide insight and examples on how they can move beyond the most obvious forms of pollution control compliance, environmental risk assessment and other reactive measures.

China claims to have the "first law in the world to establish Cleaner Production as a national policy, and to lay out a strategy for its promotion and implementation." This Law defines CP as:

"the continuous application of measures for design improvement, utilization of clean energy and raw materials, the implementation of advanced processes, technologies and equipment, improvement of management and comprehensive utilization of resources to reduce pollution at source, enhance the rates of resource utilization efficiency, reduce or avoid pollution generation and discharge in the course of production, provision of services and product use, so as to decrease harm to the health of human beings and the environment."

The CP Promotion Law is being implemented by a combination of local administrative units (provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities) and national bodies (including environmental protection, planning, science and technology, agriculture and construction). The Law involves a blend of "carrot and stick."

Inducements include recognition and rewards for success stories, product labeling, an SME fund, and technology innovation funding, funding for public education and professional training, exclusion from value-added tax (VAT) for products and materials produced or reclaimed from wastes, recognition of training and CP auditing as enterprise operating costs. As well, governments at all levels are encouraged to use their purchasing power to "buy green."

The planning and enforcement side includes incorporation of CP within regional economic blueprints, adjustment of industrial structures to a recycling economy, and promotion at local levels of increased cooperation on the part of industry. The "teeth" of the new Law are in the power to eliminate obsolete and obsolescent production technology, processes, equipment and also products that are "wasteful of resources" or "gravely hazardous to environment." The penalties of non-compliance to the Law are, however, quite moderate, with fines of up to 100,000 yuan.

The potential range of CP implementation tools identified by the NDRC is very extensive: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA); Public Environment Reporting; Environmental Indicators; Industrial Ecology; Codes of Practice; Environmental Audits; Environmental Management Systems (EMS); Environmental Accounting; Design for Environment; Environmental Labeling; Performance Based Contracting; Eco-Efficiency and Environmental Taxes. Certainly there are important choices to be made on which of these are likely to be the most effective, and on how they can be implemented in an integrated fashion within the overall system for sustainable industrialization.

Implementation guidelines for the CP Promotion Law identify ten cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Shenyang, Taiyuan, Jinan, Kunming, Lanzhou and Fuyang ) as demonstration sites. The guidelines also identify five priority sectors: the petrochemical industry, metallurgic industry, chemical industry (nitrogen fertilizer, phosphate fertilizer, chlor-alkali and sulphuric acid), light industry (pulp and paper, fermentation and beer-making), and ship building. SEPA has identified five rivers (Huai He, Hai He, Liao He, Chang Jiang (Yangtze River) and Huang He (Yellow River) and three lakes (Tai Lake (Tai Hu), Chao Lake (Chao Hu) and Dian Chi which have high priority for CP initiatives.

China is building on a full decade of experience with training and promotion of Cleaner Production. Much of this experience was thoughtfully reviewed at the 2001 Chinese International Conference on Cleaner Production . Several major implementation barriers have been identified, including the following:

• Market failure that results in a relatively weak supply and demand for CP.

• "Industrial indifference" to the concept.

• Inadequate CP knowledge and support mechanisms, especially for SMEs.

• Inadequate enforcement of environmental laws, including low fines that become part of conducting business.

• Lack of an overall operative system for CP that can engage Chinese industry at various scales including the level of individual firms, relations between firms within or between sectors, and at regional to global levels.

Hopefully, the new CP Law will reduce the barriers. The question is at what rate?

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)—Business and Xiaokang Intersecting

Corporate governance, including mechanisms for both encouraging and monitoring corporate sustainability, is emerging as a key element of globalization. Chinese firms do not fare well by comparison to global leaders in business. The recent trend internationally is to bring together a number of governance considerations under the title of "Corporate Social Responsibility" . The shift engendered in the CSR approach is that license to operate is not a given, but something that is earned. Increasingly performance is measured by a range of local, national and international organizations that use market tools and information campaigns to alter poor corporate behavior. China's corporations—whether the "Top 500" Chinese firms or SMEs—may feel somewhat removed from these pressures. But they are not, especially given China's accession to the WTO. Thus, developing a Chinese-based business case for sustainability and CSR is very important. Presumably this business case will blend both international approaches, and China's concern for equity and a social market economy.

The WBCSD's business case for CSR is stated as follows :

We believe that a coherent CSR strategy based on sound ethics and core values offers clear business benefits. These accrue from the adoption of a broader world view, which enables business to monitor shifts in social expectations and helps control risks and identify market opportunities. Such a strategy helps to align corporate and societal values, thus improving reputation and maintaining public support.

Chinese enterprises, especially those directly or indirectly controlled by the state, are subject to many governmental influences, and therefore decisions often appear to be taken for them, rather than by them. This approach probably works against the development of CSR along the lines described above. OECD and others point out the need for strong corporate governance in which decisions are taken directly by the enterprise and its board, with accountability and transparency.

Stigson (see footnote 19) raises important questions about how far a company or industrial sector should be expected to serve societal needs: What are the respective roles of business versus that of government in providing social, educational, and health services? How far along the supply chain does a company's responsibility extend? How should it adapt to local cultures? How far into the future should a company plan? These questions are important in a number of ways in the Chinese context. Two will be discussed here: the role of state corporations in the social security net, and supply chain dynamics building upon China's role as a key player in global outsourcing of industrial production.

The first is important since the national social security net, an important component for overall societal well-being in most western nations, is still weakly developed in China. State-owned enterprises have provided a considerable element of personal security for many people. And now, it is difficult to restructure some of these enterprises since there are few social security alternatives for affected people (employees are considered as privileged creditors, therefore state commercial banks have little incentive to call loans and thus transform industry). The problem is made more acute since much of the control of these state industries actually lies at provincial or local levels. Poorer regions, for example, in the northeast and western regions have little in the way of financial resources to address this problem . It clearly is an issue where expecting corporations to bear the full burden on an individual basis will not only be inefficient, but also delay necessary restructuring for some of the least environmentally-sensitive enterprises.

The supply-chain issue is important for Chinese exporters and for large Chinese firms working internationally (there will be many more of these in the future), and also for some Chinese domestically-oriented business, for example, the automobile industry. In the international marketplace, and in some developing countries as well, there is growing interest in having raw material and component suppliers to the final industrial assemblers operate in an environmentally sustainable manner. Many auto companies such as General Motors and Toyota already require this of their suppliers—wherever they may be located in the world.

Some companies expend considerable effort in capacity-building so that suppliers develop reliable levels of sustainability compliance. This is a means for technology transfer, and for assuring that sustainability performance moves steadily upwards, rather than globally downwards, as companies decentralize production. It is also a means for a country like China to brand particular sectors as being "green" or "sustainable", since, ideally, the whole life cycle of products can be covered, including the extraction of raw materials and use of energy at each stage.

Corporate social responsibility in China is still at an early stage by comparison to leading edge enterprises in Europe or some other industrial regions. Perhaps there is a residual positive benefit from some state enterprises in their commitment to providing social goods for workers and local communities. Also, there are lessons to be learned from the more progressive multinational companies operating in China. Overall, however, it is likely to be a long-term challenge for China to re-shape enterprise governance, and to ensure that broadly defined societal needs are addressed as part of the corporate business model. The xiaokang approach, if interpreted by leaders in a fashion that is actionable by business enterprises, could become a key component of future Chinese corporate social responsibility.

Transparency, Accountability and Benchmarks

Internationally, the effort to build an environment and sustainability accountability system is becoming much more sophisticated, covering several key elements of corporate behavior. The effort includes:

• Corporate sustainability reporting in which individual corporations set objectives and describe their performance in achieving them. Such reports can be rigorous and independently audited, or they can be little more than "greenwash".

• Codes of conduct or Guidelines such as the CERES Global Reporting Initiative; the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises; and the UN Global Compact. None of these very useful guidelines for corporate behaviour are legally binding, but they are shaping both expectations of business and actual business conduct.

• Certification processes including ISO 14001, the Forest Stewardship Council, and many others operating at national, international and sectoral levels. By certifying that products are produced sustainably, or that the entire corporation, or even clusters of businesses (e.g. within an industrial park) is managed sustainably, certifiers are providing at least some level of assurance that a business takes environment into account. There are various levels of credibility with such processes.

• Development of specialized corporate indexes, including the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, the Domini 400 Social Index (DSI), and the FTSE4Good benchmarks. Such indices are meant to inform investors and provide an understanding of how share value can be influenced by environmental and sustainability performance.

• Ethical trading initiatives opening markets for marginalized groups, and guaranteeing good return for sustainably-produced goods. This movement, started by a number of civil society organizations opens options for consumers in rich countries to buy products that have been produced in an environmentally appropriate way, and with a reasonable share of the retail price actually being received by the producers in developing countries. Shade-grown, organic coffee is one example of a successful ethical trading effort now widespread in Latin America.

• Watchdog organizations examining corporate performance including governance and corruption, human rights, and environmental stewardship. The Internet has opened important communications channels for acquiring information on corporate and governmental actions, and rapidly disseminating that information to consumers and non-governmental organizations world-wide.

Despite this progress, a reality is that internationally-accepted benchmarks for industrial sustainability are still in short supply. Many corporations—even within the northern European countries considered to be the hotbed of concern for corporate responsibility—are wary of investing substantially in processes that may not be backstopped by official recognition in trade agreements, regulations or other instruments normally employed by governments.

But another reality is that consumers and non-governmental organizations hold considerable power within the marketplace. And analysts concerned about a company's performance are beginning to take note of measures such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. Chinese business enterprises should be considering how to engage in these voluntary, market-driven approaches. Such approaches certainly will be of growing significance domestically and internationally. It is to China's advantage to influence the nature and extent of benchmarks that might be applied to its industries in the future. There is a need to define clearly what is reasonable, and what is not.

At present, most Chinese firms operate without very clear guidelines on how well they are performing with respect to either environment or sustainable development. A growing number of firms and industrial estates are engaging in the ISO 14001 certification process. But signals sent by governments are not consistent, despite major improvements in recent years. Nationally, the coordinating function among governmental ministries is weak. Thus, individual sectoral policies prevail, to the net detriment of cross-sectoral sustainable development strategies.

The problem is exacerbated by the important role local government plays in attracting industry to a region or municipality, and then in regulating its activities. Local governments sometimes are in a conflict of interest as they struggle with sustainable development strategies and industrial implementation. It is believed that environmental considerations are frequently downplayed, even to the extent of returning fines to industries found guilty of pollution. The desire to retain industry at any cost cannot be overstated, at least within poorer areas. Such observations are well understood by both the Chinese government and international agencies .

These considerations cannot be dealt with in isolation from broader issues of industrial reform. Corporate governance within China is neither strong nor very independent, swayed as it is by local political interests, on-going support for some non-competitive state enterprises, and by the influx of foreign direct investment from sources in other regions of Asia where transparency and accountability are weak.

URBANIZATION AND SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIALIZATION

Urbanization accompanied the rise of industrial societies throughout the world, but in China's case there is an unprecedented transition ahead. By 2020 it is anticipated that only 30% of the labour force will be engaged in agriculture, instead of the current level of 50%. Urbanization over the coming two decades could bring as many as 300 to 400 million more people into cities. Most will be attracted away from agriculture and into industrial and service occupations. But industry will be the driver. Location of industry is therefore a key determinant.

Fostering of town and village enterprises (TVE) has been a major strategy to spread industrial development into the countryside. And the current drive to locate additional industry in areas beyond the east coast should spread at least some of the opportunities and impacts of such development. In the drive for equitable sharing of economic benefits, and for enhancement of human and social capital, it is likely that the most significant gains involving industrial contributions will be in the cities rather than the countryside.

Sustainable industrialization strategies in China have to focus on the quality of life, the balance between creating rural and urban opportunities, and the economic, social and environmental impacts of industrialization on urban development. Industrialization provides much of the financial wealth for both infrastructure and human development needs in cities. But for many industrial areas of the world, urban decay, including abandoned factories and contaminated "brownfield" sites , declining condition of infrastructure and inner city poverty, has been the consequence of the last century's industrial development.

There are some good reasons why China should be able to do better than simply repeat this unfortunate saga of "industry first, address problems later." These reasons include: China's well demonstrated ability to learn from existing experience elsewhere; the national commitment to sustainable development; some very positive environmental improvements within cities as a consequence of existing policies and planning; monitoring and reward systems that recognize the achievements of individual cities; and the relatively small per capita ecological footprint of urban Chinese residents (although consumption is increasing dramatically with income).

Yet it is apparent that some of the worst urban pollution in the world is found in several Chinese cities. In the mid-1990s, the WHO rated 8 Chinese cities as being among the 10 most polluted in the world. Most cities are caught in a complex transition involving transportation networks that are likely to become overburdened supply routes for industrial suppliers and products as well as for burgeoning populations of private automobiles. Supplying the physical needs for urban infrastructure, such as cement and steel, in an environmentally sustainable fashion is, and will continue to be, a major challenge for Chinese industry. Of great significance is the competition on the part of industry for land and water in urban and suburban areas.

Urban and Industrial Planning

China is probably the most exciting country in the world in which to be currently engaged in urban planning and development. Some cities such as Beijing and Shanghai are competing for the world's recognition as outstanding urban centres, just as Singapore did two decades ago. Others such as Dalian are determined to build a reputation based on environmental quality. In the region of the Pearl Delta a very large scale proposal exists to create two "metropolitan rings", formed by Hong Kong-Shenzhen and by Guangzhou-Foshan. These "rings" have enormous infrastructure and environmental implications, but also would have important benefits to the region for industrial innovation. We can expect to see urban design carried out at a scale no other country in the world is prepared to even contemplate.

Much of the future industrialization, however, will be tied to smaller centres—cities that might have significant constraints such as water shortages, airshed characteristics that retain pollutants, and fragile environmental conditions such as significant biological conservation needs in nearby ecosystems. These problems are already evident and an important consideration in western development plans, and there are successful experiences to draw upon from existing development, for example, Hainan Island and the City of Dalian.

Urban planning also has to take into account impacts of industrial development on the countryside, especially suburban development and transportation corridors that include road and railway networks, river transport, and energy transmission corridors for pipelines and electrical lines. The advent of just-in-time industrial production systems will place considerable stress on reliable transportation networks.

Urban environmental planning interlocks with sustainable industrialization in a number of ways:

• Sophisticated physical planning tools (e.g. GIS) are readily accessible within China and widely used. These can be further refined and used to build scenarios of the impacts of industrial growth and alternative patterns leading to both sustainable industrialization and sustainable cities.

• Incentive approaches as well as command and control instruments such as zoning are important for planners to consider. This is particularly important for pollution control, water conservation, and for development and maintenance of green spaces.

• There will be increasing demands from urban residents for a voice in planning decisions. Planning will need to be done in a transparent fashion, particularly concerning environmental impacts and social matters.

• Opportunities to incorporate industrial ecology considerations are already being taken within urban planning, but not always systematically. Much more can be done along these lines.

• Urban pollution control strategies are broadening to consider strategies such as reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, the interaction of pollutants across the three media (land, water and air), and the need to drastically reduce solid and hazardous wastes. Cities that can plan in this fashion become important contributors in the Circular Economy.

• Clean environment is a marketable component of urban attractiveness when it comes to business location, tourism, and movement of skilled labour. Enhancing or creating such attributes so that cities have a well-recognized identity of environmental and social quality is an important task for planners working in concert with Chambers of Commerce, industrial leaders and others.

These topics will be covered in more detail at the 2005 CCICED AGM when the theme is anticipated to be sustainable urbanization. Here we will focus on several matters pertaining to sustainable industrialization.

Water and Land

Addressing Water Scarcity and Quality

Water is an increasingly scarce resource that affects development in urban and industrial centres throughout the world, including those located in some of the wealthiest countries. Industry tends to pay for water at a level much closer to real costs by comparison to agriculture. Even so, the cost of water levied to any user rarely reflects the range of environmental benefits that might be lost through its use, especially if water quality is degraded. These issues have been explored exhaustively by international agencies, national governments and in a series of global water forums . Pricing of water has been a topic of concern for some time in CCICED, with useful observations from several Working Groups in the past, especially the Working Group on Environmental Economics.

Solutions proposed include both structural (e.g. water control means such as dams) and non-structural (e.g. conservation measures and land use zoning) elements. Together, the range of solutions is considered as integrated water management, a theme promoted globally, but with limited success in applications to date within either rich or poor nations.

Another topic of broad concern being explored internationally is public-private sector partnerships for delivery of water services, including building of infrastructure, water supply and sanitation. This is an area where private sector efficiency can be coupled with governmental supervision to ensure the public trust is maintained and equity issues are addressed. Industrialization strategies may include development of water resources for multiple purposes, so that communities may benefit as well as industry. Despite the attractive nature of public-private partnerships, they can be controversial, especially when profits are seen to be derived from a public good.

According to the World Resources Institute, 300 of the 640 major cities in China already face water shortages, with consequent losses of about 120 billion yuan per year in industrial output. Human health impacts multiply this figure. Furthermore, the very limited per capita supply of water may be on the decline in a number of cities, since groundwater depletion and contamination have occurred at a large scale. The discharge of toxic industrial wastes into water that ultimately becomes used for drinking or irrigation, undoubtedly contributes to high rates of certain types of cancer, for example in Qidong and Fushun regions. China's water demands are expected to grow by 2 to 3 % annually over this decade, with a demand increase of about 120 million m³. Much of the demand will come from industry, and it will be difficult to address, even with major engineering efforts, for example, to divert water from the south to the dry northern areas.

The Ministry of Water Resources has a seven point framework for action that has significant implications for industrial development : (1) long-term supply and demand planning and assessment; (2) water source, water quality and ecosystem protection; (3) groundwater conservation and sustainable use strategies; (4) assured domestic and industrial water supply; (5) pollution control and wastewater recycling; (6) coping with effects of climate change; and (7) management reforms.

The extent to which water issues are linked mainly to engineering solutions, or to mechanisms involving protection and enhancement of ecological services, such as increasing water storage in wetlands, is a debate just beginning to find its voice in China. Pricing has to be an important part of action for sustainable water management. Sustainable industrialization is highly dependent upon the outcome of action to conserve and better utilize water. Ideally, therefore, industry should be a leader in helping to shape outcomes.

Industrial Stewards of Land

The impact of industry on land issues is considerable in all parts of the world. Factors include regional and local land development, access, future uses, economic and ecological values, displacement of people and indirect impacts, for example, of land associated with transportation networks, solid waste disposal, reservoirs and other infrastructure. Liability associated with contaminated "brownfield" sites has become an expensive and contentious issue to deal with, especially in North America and in both eastern and western Europe.

In the U.S.A. the clean-up of toxic sites often becomes the responsibility of whoever has the deepest pockets and some association with the land. In Eastern Europe during much of the 1990s, concerns over liability for clean-up of badly contaminated sites held back investment in existing industrial operations by foreign investors. And many of the human health impacts associated with contaminated lands are not fully factored into costs of land mitigation. An important point which emerges from this experience is that land ownership, title transfer and investment possibilities become complex if uncertainty arises over who actually "owns" the liabilities associated with the land.

Sustainable industrialization should incorporate a comprehensive approach to land use—an approach that could be characterized as industrial land stewardship. Many companies already take such an approach, including some leaders within the mining and forest industries . The Ford Motor Company has redeveloped its massive Rouge River industrial complex in Michigan, with environmental improvement and manufacturing innovation as complementary objectives. Long-neglected, often abandoned industrial sites in many cities are now seen as among the most valuable lands, sometimes with new, less polluting industries as tenants, along with residential and light commercial land uses. Denmark and other European countries provide very successful examples.

Clearly, local governments, both rural and particularly urban, have to play a proactive role in order for industrial land stewardship to be optimal. The location and conditions under which industrial parks are established, provision of common waste treatment facilities, and the development of local and regional transportation networks that do not take up excessive land are important examples that are best resolved at this level. Unfortunately, the outcomes—even where there has been an extensive investment in planning—often leave much to be desired. An example is the congestion on highways as a consequence of the "just-in-time" demands of manufacturing industries, and the desire to have the greater flexibility of delivery by trucks rather than by railroad transportation. Another is suburban land sprawl that arises from the desire of industries to build on "green fields" and the desire of residents to move from decaying centres of cities.

National and state/provincial governments have often taken on a "silent partner" role in relation to industrial environmental malpractice, for example, by not enforcing laws, or by encouraging bad land use decisions through perverse subsidies such as low land pricing. Governments can be highly proactive, but, ultimately contributing to unsustainable business situations, for example, by attracting industry to locations where land or water conditions may be unsuitable. Appropriate roles for national government include: creating a national inventory of contaminated sites, with strategies and plans for their restoration and future uses; development of a robust strategy for reducing and, where possible, eliminating hazardous wastes; and, through partnerships, creating examples that truly do work, often with remarkable financial return. An outstanding example in Canada is the redevelopment of False Creek, a highly contaminated brownfield area in Vancouver, now in high demand as a residential and commercial area. Japan is a source of many additional examples.

China has already demonstrated a remarkable capacity to develop and redevelop lands, especially in the cities. And with much of the country's industrial development still ahead, the opportunity exists to avoid creation of new toxic areas, to plan for co-location of industries (in order to take advantage of byproduct synergies and to reduce transportation needs), and to plan cities and suburban areas that provide for both citizen and industrial needs.

There are existing problems that need to be overcome. One very important issue is hazardous waste management. There does not appear to be a full inventory of existing problem areas. Indeed, it is quite possible that nasty surprises may emerge in the years ahead. Hazardous wastes are covered under several pieces of Chinese legislation. The siting of toxic waste treatment centres, and the conditions and management of municipal land fills need careful attention. The culture of industrial development will need to shift so that both state-owned and private enterprises see themselves as stewards, prepared to invest in proper land care, and to leave sites in better condition than when they arrived. Special restoration funds set aside by companies for land management once industrial activities are completed is a workable mechanism that deserves attention in China.

A peculiar problem, highlighted in the recent OECD review of China's domestic economy , is the nature of land use rights granted to industrial operations rather than ownership, which is retained by the state. For many enterprises undergoing restructuring, these land rights may be their only valuable asset. But value varies according to location and therefore hinders restructuring for those located in low value sites. Thus old, poorly located industries continue past their desired lifespan since they do not have the funds to meet social costs and other expenses. It has been suggested by the World Bank that an administrative fund could be used to pool the revenues from sale of both high and lower value land use rights taken back from bankrupted enterprises in the region. The funds could then be used to meet social costs and rehabilitation fees of poorly-located industries wishing to declare bankruptcy.

Eco-Industrial Parks

The concept of industrial ecology is now well understood in various parts of the world, including China. There are several important points to this approach, as noted by J. Alan Brewster :

• "An industrial system should be viewed not in isolation from its surrounding systems, but in concert with them."

• " No 'wastes' but only residual materials that can be used to produce other useful products."

• "Looking at cumulative impacts of industrial sectors."

Industrial ecology can be examined at various levels: enterprise (e.g. eco-efficiency); between enterprises (e.g. eco-industrial parks, product life cycle, responsible care); regional and global (e.g. budgets and cycles for dematerialization and decarbonization).

Of these topics, the one for discussion here is sometimes described as "industrial symbiosis"—the reason for bringing together various industries into close proximity. Standard industrial parks are giving way to a new model, or are being renovated to become this model, called an eco-industrial park (EIP).

There are many examples throughout the world. Chen et al., describe such parks as "an industrial system of planned materials and energy exchanges that seeks to minimize energy and raw materials use, minimize waste, and build sustainable economic, ecological and social relationships.

Tsinghua University has been actively involved with such eco-industrial parks, working with several models (see footnote 36):

• Shandong Province – transforming a traditional industrial zone to an EIP, reducing water use by 40% and other major pollutants.

• Zhejiang Province – Juhua Group, one of China's largest chemical enterprises, has developed material exchange among its chemical plants on a 600 ha site, where some 180 chemicals are produced.

• Guangdong Province – Nanhai greenfield development site involving four types of environmental businesses (environmental equipment manufacturing, environmental protection research and services, waste recycling, and environmentally-friendly products).

These facilities go hand-in-hand with urban development since they are a way of generating employment, providing tax revenues, and contributing directly to infrastructure development. And they are clean, generally adding to rather than detracting from urban environmental quality. It is also a means for attracting a mix of foreign and domestic investment that can have a beneficial capacity development and technology transfer component.

The EIP concept, and even grander scale efforts such as the eco-province and eco-cities concept now being promoted by the Chinese government will undoubtedly become much more commonplace. Undoubtedly they will contribute immensely to sustainable industrialization. Since much of the industrial capacity will be installed in the next decade or two, there are excellent opportunities to cluster appropriate combinations in order to promote synergies and industrial efficiency. It may, however, take considerable effort to add the dimensions that will help to promote xiaokang.

ENVIRONMENTAL INDUSTRY SECTOR

For a number of years the development of environmental industries has been considered one of the fast-rising components of industrialization worldwide, with a potential on the scale of a trillion dollars. Much of the future growth is predicated upon continuing need for water supply and waste treatment, often based upon conventional technologies. But the approaches are changing as a result of shifts in both supply and demand. On the supply side, many new technologies and services are emerging, stimulated particularly by the demand side focus on sustainable development and the need to move towards "no waste" situations. As well, there is a broadening of definition to include "green" products and technologies based on "renewable" resources such as biomass and wind or solar energy.

In the future, environmental industries will move away from providing "end of pipe" pollution control solutions towards transformation of industrial processes and consideration of whole industrial landscapes in order to achieve byproduct synergies and more satisfactory co-existence with communities.

China is aggressively developing an environmental industry sector with the intent of not only meeting domestic needs but also finding international markets. This is an ambitious goal, but quite realistic given the projected needs associated with economic growth generally, urbanization and industrialization in China and other parts of East Asia. The growth and characteristics of China's environmental protection industry is the subject of a CCICED Task Force Report to be discussed at this AGM.

It is clear that Chinese environmental industries are still mainly at the SME level. Many could be considered at the "incubator" stage. With the opening of China's domestic market to foreign environmental protection companies, there may be stiff competition and a need to pursue strategies such as joint ventures. It has been suggested that their current level of technical knowledge lags 5 to 10 years behind international levels.

Demand for environmental protection services is a critical factor for growth of this sector. Government can assist in a number of ways, including consistent application of law enforcement, use of its purchasing power to stimulate production of "green products", inclusion of environmental considerations in major developments and demonstration efforts, choice of new technologies such as wind power, investment in R&D, ecological construction and restoration, and in the application of various incentives via pricing, tax and subsidy systems. Many of these areas are now well recognized by the national government and it is likely that a reasonably coherent approach will emerge. One of the most difficult areas is devising changes in the fiscal system to remove perverse subsidies that promote unsustainable practices and old technologies, but taking care not to introduce new distortions, and investments or incentives for new businesses that are doomed to failure.

The treatment of environment by local level governments deserves scrutiny. Markets need to be national in scale, and local protectionism or lack of concern for environment will work against development of a strong national environmental protection sector of industry. Also, as the sector matures, there will be a greater need for access to financial markets for necessary capital. There likely is a need to build greater understanding of the environmental protection sector so that financing does not become a bottleneck.

The development of the environmental protection sector should go hand-in-hand with the journey towards sustainable industrialization in China. It is a win-win proposition. By stimulating the development of this sector, a surprising number of jobs will be created, and the various objectives of environmental improvement should be met more quickly. And, as the sector matures, it should be possible to further refine the goals of sustainable industrialization, since new environment and sustainable development technologies and experience will be accessible within China.

ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES AND SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIALIZATION

Even as China builds its strategy for sustainable industrialization, many of the OECD countries are becoming post-industrial societies in which knowledge, entertainment and information technologies are currently playing a huge role. Yet, as these societies change, it is clear that it is not industry disappearing, it is industry being radically transformed. What should China learn from the international experience with these trends, especially those which link emerging technologies and sustainability?

One clear trend is towards economies that are much more aligned with life processes. Biotechnology, while controversial in many aspects, is likely to become much more significant in its range of applications, including industrial processes (e.g. use of modified enzymes) and bio-based products. Industrial biotechnology is defined by OECD as "that set of technologies that come from adapting and modifying the biological organisms, processes, products and systems found in nature for the purpose of producing goods and services."

Biotechnology promises to create products and industrial processes with performance characteristics that can be delivered by conventional industrial chemistry. Bioremediation to turn wastes into products offers great potential in food industries, energy, mining, etc. The major international trend is towards a new "Biological Economy" that will address biological diversity maintenance, sustainable industrialization, and sustainable natural resource use as interlocked subjects.

Another new theme, still in its earliest stages, but expected to develop rapidly, is the move towards understanding the properties of matter at the smallest scales, molecular to atoms, with the intent of using these properties to drastically dematerialize products and industrial processes. The emergence of nanotechnology as an important field has just begun. Yet some predict an amazing transformation of industry in the coming decade. Examples include: pumps operating at 20 to 50% of existing energy needs; 100% recyclability of dangerous chemicals, "molecular machines (molecules acting as machines) that activate and deactivate catalysts for more efficient chemical manufacture, inexpensive solar power collectors using roads and building windows, and nano-scale computing technologies with much greater capacities than any current machines.

The remarkable array of alternative energy pathways already becoming available represents a third critical trend. The hydrogen-based fuel economy, bio-based fuels, solar and wind energy alternatives, and extreme measures for energy conservation are examples that have been discussed in CCICED meetings. During the current AGM the presentation of the Task Force on Transforming Coal for Sustainability will propose new options that have major implications for industry. With decarbonization of industrial processes being an additional important issue, new R&D directions are being set out in most OECD countries and in China. Decoupling energy demand from increases in human activities will continue to be perhaps the greatest social and technological challenge of our times.

These advanced examples, and others that might be mentioned, should provoke much thought and discussion on how best to address investment in the necessary R&D and commercialization of new technologies. Some may warrant attention at the earliest stages, perhaps involving products and approaches that are more advanced than those in OECD countries (for example on some aspects of alternative energy and of biotechnology.) In other cases, it may be wise to invest more cautiously, when it is clear which technologies are likely to be the most productive in meeting China's sustainability needs. It should be clear, however, that it is a more diverse set of advanced technologies than those classified generally as information technologies, the major focus during the 10th Five Year Plan.

The role of new technologies that support the transition to sustainable industrialization does not stop with advanced production processes. Perhaps the greatest contribution will be if these new technologies actually do produce products of great utility for reaching xiaokang objectives defined in the broadest sense of quality of life. If health is improved, if products are made much more durable, if people's ability to communicate cheaply and over long distances is improved, and if knowledge can be made more accessible, for example through very inexpensive computing devices and networks, then the investment in new technologies will have proved to be extremely valuable.

INDUSTRY, TRADE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

China already provides more than 4% of the world's exports and this figure is expected to rise to more than 7% by 2007. The remarkable feature of this growth is that it will come from a very diverse range of products, including processed foods, garments, chemicals, manufactured consumer goods such as electronics, and, heavy machinery. Thus China has a large stake in how WTO treats various aspects of environment and sustainable development, and also, of course, in how its trade competitors and those countries importing its products address these issues, including the use of various mechanisms such as non-tariff trade barriers.