2004-10-31李瑞Source:

Executive Summary

A. Protected areas are essential to the development of China

The future of China depends on maintaining healthy ecosystems. Natural or reconstructed ecosystems ensure China's supplies of fresh water, energy and nutrients, its banks of crop pollinators, pest-control agents and genetic resources, and its capacity to sequester carbon, maintain quality of life and provide many other essential goods and services, including flood control. But all these functions can be disrupted by inappropriate forms of development. Recognizing the many values of ecosystem services, governments in all parts of the world have allocated certain sites for maifntaining the biodiversity upon which those services depend. Such sites, known collectively as "Protected Areas", are managed through legal or other effective means to deliver long-term benefits to humans. They help to define the national culture, assist economic development among rural people, and serve as destinations for tourists. In total and conservatively estimated, the economic value of ecosystem goods and services is more than 30% of national GDP, and much of this is linked to protected areas and their management in the context of the overall landscape and economic development.

B. China's current system of protected areas is not delivering sufficient benefits

China has made great progress in establishing protected areas, including nature reserves, scenic landscape and historical sites, non-hunting areas and forest parks. Protected areas now cover over 15 percent of the country, most of this in the sparsely-populated west. However, there has been no comprehensive evaluation of their actual or possible effectiveness in conserving China's biodiversity; preliminary analysis reveals significant gaps in the coverage of species and habitats, and major problems within the existing system. A large proportion of the protected areas are small and isolated, limiting their value for species and ecosystem conservation. Meanwhile many important opportunities to protect areas for their ecosystem services have been missed.

The protected-areas system remains isolated from land use plan and economic development programmes by the government. Protected areas' management and funding mechanisms are only weakly linked to the full range of protected-area functions. Current legislation and management practices lead to conflicts with local people, poor enforcement of laws, little or no coordination with other economic sectors, and, ultimately, loss of ecological and other protected-area services such as climate regulation, watershed protection, erosion control, biodiversity conservation and tourism earnings. Together these will cost China many billions of US$ in potential revenue and social benefits over the next decades. Many protected-area staff are low in technical capacity and morale, with dim prospects for career progress. The diverse functions of protected areas are poorly understood by the general public, including those who make decisions affecting their viability.

C. Towards a modern system of protected areas

China should work towards a protected-area system fully representative of the country's wild species and ecosystems, and their beneficial functions. It should encompass a range of management categories, from strictly-protected to multiple-use. Such a system will have:

D. How to achieve the new system

The Evaluation Report and a number of technical papers give the Task Force's recommendations in detail. The key recommendations are as follows:

a. Establish a comprehensive legal framework for an advanced system of protected areas based on the full range of protected-area objectives

China should draft a broad, framework Protected Area Law under which more specific legislation, including the nature reserve law currently under preparation and regulations on other types of protected areas should be included. It is also urgent to categorize protected areas, adapting the IUCN category, to set up different management objectives according to the overall needs and feasibility. The PA Law should specify legal procedures and criteria for establishment of various categories of protected areas, based on their management objectives, supervision and evaluation mechanisms, methods of funding, and participation of local communities and the wider public.

b. Design a new and comprehensive protected-area system and build a high-level multisectoral alliance to support it

China should design a protected-area system that designates new protected areas where needed, including strategic corridors preserving key ecological linkages, and provides for changes in the categories, zoning or boundaries of existing ones. The PA System Plan should be integrated into the governmental "Five Year Plans" at national, provincial (and municipal) and county levels. China should also form an above-ministry-level and cross-sectoral alliance to ensure the integration of protected areas and overall land use and development planning, coordination among line ministries, and supervision of protected-area effectiveness. This alliance might follow the model of the former Environment Protection Committee of the State Council. Provincial Environmental Committees should carry out essential conservation issues such as coordination, supervision and evaluation of protected-area plans and performance. Regarding supervision and evaluation of protected areas, some effective international measures for world heritage site management can be applied.

c. Implement a variety of funding mechanisms clearly linked to ecosystem services delivered

China should develop innovative public funding mechanisms for protected areas that allow payments for ecological and other services realized at various distances from the protected areas – at the global, national, regional and local levels, as well as through direct cash income such as from concessions to tour operators. It is recommended that quality assurance mechanisms be established so that no inappropriate sites are given protected area status, and plans and results are subjected to strict evaluation linked to funding. Funding presently available for infrastructure development in protected areas should be diverted to uses more compatible with their prime objectives.

d. Ensure that people benefit, and do not suffer, from living near to protected areas

In establishment and management of protected areas the system must recognize the many relationships between resource management and the needs of rural people. All decisions taken by protected-area managers must consider the socio-economic context of the protected area, and protected-area management plans should be prepared on the basis of consultation with stakeholders, giving particular attention to income sources for local people. Special attention should be given to the plight of local people whose relinquishment of the use of protected-area land or other resources has led to poverty or other difficulties.

Other recommendations in the report cover the need for a career structure and institutionalized training in the wide range of skills required by PA staff, and the importance of an protected area information service system, as well as public information and involvement in a protected area system.

Taken together the actions listed in Section 5 of the Evaluation Report will lead China towards a modern effectively-managed system of protected areas that will provide sustainable benefits at local, county, province, and national levels, and conserve biodiversity and ecosystem services. Achieving that aim will require a considerable amount of political will to counteract current institutional inertia, and narrow and short-term sectoral interests.

1. Introduction – Broader Roles For Protected Areas

1.1 Global experience

Almost all countries in the world now recognise the wisdom of designating protected areas (PAs) for conservation of species and their habitats, for maintaining natural ecological processes, or for their geological, scenic or cultural values. All countries that have ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) have an obligation under Article 8 to establish representative systems of PAs. Article 7 of the CBD further requires member parties to monitor biodiversity and conservation initiatives such as PAs, and Article 17 obliges member countries to share such information globally. Under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, the World Heritage Convention and the Man and the Biosphere Programme signatory countries take on further obligations and commitments with regard to PAs.

The World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) compiles information on the global PA system and, with The World Conservation Union (IUCN), maintains the United Nations (UN) List of National Parks and Protected Areas. The World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN undertakes the role of assisting countries to improve the management, monitoring and reporting of their PA system. Over 11% of the world's land area of the planet is now designated as some kind of PA. IUCN have standardised information on PAs by assigning all sites to one of six recognised management categories and have published guidance on applying key criteria to assign such categories (See Paper of "Applying the IUCN Protected Area Category System" in China in the book of China's Protected Area).

At the Vth IUCN World Congress on Protected Areas in Durban in September 2003 the 3,000 participants, including nearly 100 delegates from China celebrated, voiced concern and called for urgent action on PAs in the Durban Accord (see Paper of "Durban Accord of the Vth World Parks Congress" in the book of China's Protected Area). They called for a "new paradigm" – a fresh and innovative approach to PAs and their role in the broader conservation and development agendas that will forge " the synergy between conservation, the maintenance of life support systems and sustainable development". The delegates expressed concern at the high rate of loss of natural areas and biodiversity and the lack of PA status for many areas of irreplaceable and immediately threatened biological diversity, that many PAs exist more on paper than in practice, that development plans often do not include attention to PAs, and that many costs of PAs are borne locally – particularly by poor communities – while benefits accrue elsewhere and remain underappreciated.

1.2 Multiple functions

Protected areas perform a wide range of functions and in a well designed system have specific objectives assigned to them when they are designated. Usually PAs address a number of subsidiary objectives besides their main objectives. The following examples indicate the range of possible objectives:

• Provide resilience to the environment through maintenance of valuable ecosystem services to surrounding and downstream areas, through protection of soil and watersheds for example, and effects on microclimate

• Conserve populations of animal and plant species in natural environments that allow for their continued natural selection and evolution. Gene pools of cultivated plants and domestic animals are important here, and the conservation of the widest range of species is insurance for the future in terms of as yet undiscovered sources of medicines, foods or other products.

• Protect representative examples of ecosystems

• Protect important staging areas for migratory species

• Provide safe breeding areas for species that disperse and in some cases are harvested elsewhere in a sustainable way

• Protect local cultural links with nature

• Provide sites suitable for development of eco-tourism and accompanying economic opportunities

• Provide sites where people can experience the aesthetic and therapeutic values of wilderness, and enjoy themselves in and take inspiration from wild settings

• Protect natural resources of plants and animals that can be harvested in a sustainable way in situ

• Provide opportunities for public education and awareness and living laboratories for continued biological exploration and study

• Protect sources of potentially valuable genetic resources

Almost all PAs serve important ecological roles quite apart from their original established objectives. For example, a PA may be established to protect the breeding area of rare cranes and this biological value remains its chief conservation objective. However, the site may be a crucial water "sponge" in a river's catchment and its protection may serve a much greater contribution to the regional economy through such ecosystem services than its biological conservation purpose. Recognising this more important ecosystem role affects how a site should be managed and can help PA managers to align themselves with much stronger political forces than their own small administration.

The IUCN Categories for Protected Areas (see Paper of "Applying the IUCN Category System in China" in the book of China's Protected Area) demonstrates the range of objectives that different kinds of PAs can meet, and represents varying degree of human intervention ranging from a strictly protected area to a sustainable use reserve. It underscores the fact that PAs belonging to different categories are equally important and no one type is to be preferred over the other, and facilitates international accounting and comparison.

1.3 Economic benefits of protected areas to national economies

The economic costs of environmental degradation have been estimated at 4 to 8 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in many developing countries. During the 1990s, 670,000 people – almost all of them in developing countries – died as a result of severe climatic events, 90% of which were water related, such as floods and droughts.

The economic and social impacts of floods and droughts have increased over time as a result of human activities that tamper with important stabilizing and resilience providing ecosystems (e.g. extensive drainage of wetlands that otherwise would have absorbed floodwater, excessive logging and deforestation leading to wind- and water erosion with subsequent land slides, floods and local climate change). Overgrazing of fragile rangelands and conversion to irrigated agriculture or pastures are leading causes of land degradation, desertification, loss of biodiversity and loss of economic opportunities for job creation and poverty alleviation. The World Bank estimated that direct economic losses in developing countries due to such ecosystem mismanagement in the 1980s equalled the overall foreign aid disbursements to those countries; and also estimated that the costs of preventive, corrective and rehabilitative measures to prevent such damage would have been between 25% and 50% of the losses.

Establishment and effective management and maintenance of PAs constitute important and significant preventive, corrective and rehabilitative actions in national strategies for sustainable economic development. Box 1 below and Table 1 give some idea of the extent of benefits and the range of stakeholders in PAs, using Chinese examples.

BOX 1 Earning power

Economic valuation studies have calculated that Wolong Panda Sanctuary could earn $4 million per annum from ecotourism (Swanson 1999, CCICED report). Analysis of the value of watershed conservation of the protected forests of Xingshan county in Hubei indicated a service value of $255.4 million per annum (BWG report to CCICED, 1997).

Table 1. Examples of the range of benefits and stakeholders for a typical NR established for Giant Panda conservation in Sichuan, China

|

Function |

Type of benefit |

Beneficiaries |

|

Carbon fixation |

Reduced global warming |

Entire world |

|

Protection of water sources |

Greater water security |

300 million people |

|

Flood reduction |

20 million flood-prone downstream people | |

|

Raised water table |

10,000 local resident farmers | |

|

Eco-tourism destination |

Raised tourism revenues |

International airlines, tourism dept. capital hotels, domestic transport and restaurants, PA income, opportunities for local community |

|

Protection of rare plant resources including useful medicines |

Enhanced access to genetic resources |

Local medicine collectors, CTM industry, patients dependent on medicines, research community, drug companies, global community |

|

Protection of giant panda |

Existence value and raised tourism appeal |

National pride, Tourists, tour operators and nature lovers worldwide |

|

Protect wintering migrant birds |

Preserve threatened global populations |

Distant PAs at other end of migration pathway e.g. in Australia or Siberia. |

1.4 Distribution of costs and benefits

An effective PA system is invaluable to a nation, yet the people living in the immediate vicinity of PAs often "pay for" the benefits of the nation or of people distant from the PAs - in cities downstream for example – through being denied economic development opportunities in the PAs themselves. Some benefits may be very important but the stakeholders very distant. The stakeholders are not merely the immediate ring of local communities, so governments have attempted to develop policy that balances the various benefits and costs in a fair manner for the overall good.

If properly managed and maintained, PAs can provide significant local employment and business opportunities as wardens and other PA staff, tourist guides, hotel and restaurant staff, and in transport, handicraft production and reir facilities and other commercial services. Such opportunities are particularly important near remote PAs where jobs and income alternatives are scarce and subsistence livelihoods hard, but where human populations are high even well managed ecotourism in and around PAs is often insufficient to provide adequate livelihoods for many.

As the numbers of PAs worldwide increases and growing development demands further intensified the pressure on land resources, the capacity of government departments to cope with the management and conflict issues around so many sites has become overburdened. As a result, governments have been experimenting with higher and higher levels of people participation in PA management or co-management. The results are mixed: much depends on the particular circumstances at each individual protected area.

Fiscal mechanisms and perverse subsidies that allow for payments at the local level for the benefits accrued elsewhere are being tested in various places. There is considerable accumulated experience worldwide from PAs that have developed innovative funding mechanisms combined with management regimes to secure a fair share of revenue and benefits for local stakeholders. Examples of such cases are provided in the document Financing Protected Areas: Guidelines for Protected Areas Managers (Financing Protected areas Task Force, WCPA, 2000) (see Paper of "Financing Protected Areas – Recommendation of the Vth World Parks Congress" in the book of China's Protected Area). When choosing between indirect forms of benefits, such as assistance with establishing new livelihoods for example, and direct benefits in the form of cash in compensation, for example, for lost opportunities, there is evidence that direct payments are more effective in reducing pressure on PAs and at the same time satisfying local residents (see Paper of "On Payments to Poor Stakeholders for Sustainable Use of Protected Areas" in the book of China's Protected Area).

There is no panacea: and responsibility for poverty alleviation does not lie with PA management authorities alone. Poverty has to be addressed through a holistic and landscape approach to development.

1.5 Protected areas only viable in the context of the landscape

PAs are important, but are insufficient alone to guarantee the conservation of biodiversity and the provision of ecological services. Many of the threats to species and the integrity of natural ecological processes arise from outside PAs, so conservation requires a landscape approach that puts PAs and their management in the context of the surrounding land uses and land use rights. Further, many species, particularly migratory ones, have ranges far bigger than individual PAs, and their conservation may require actions at surrounding (or distant) sites. Good planning can reduce some of the risks: small isolated PAs lose component species to exploitation, ecological deterioration and demographic catastrophes, and because small populations can lead to fast genetic drift, inbreeding, narrowing of genepools and demographic catastrophes (the number of species that can be supported is proportional to the area of habitat), but such risks can be managed through corridors linking PAs with other PAs or with patches of suitable habitat, and through habitat management and other conservation measures around PAs. In some cases transfer of individuals between isolated patches of habitat may be desirable to achieve outbreeding. In general the risks of relying on ex situ conservation actions such as captive breeding, are high: in situ conservation maintains the natural selection pressures on a species in its normal habitat.

2. Status of Protected Area System in China

2.1 Types, numbers and distribution of protected areas

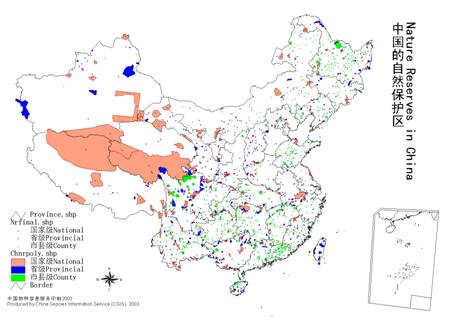

China has been active in the establishment of PAs since the first nature reserve (NR) was established in Dinghushan in Guangdong Province in 1956. Since then new PAs have been added to the national coverage, slowly until 1979 and then rapidly after the Cultural Revolution (see Fig 2 and paper of "A Review on Management System of China's Nature Reserves" in the book of China's Protected Area). There are now over 1 900 terrestrial NRs covering over 13% of the land area, 80 marine NRs, and over 2000 other types of PAs, including forest parks (1 476), scenic landscape and historical sites (SLHS) (690) that account for a further 2% of the national territory, so China has designated ca 15% of its land area as protected, somewhat higher than the global average. Over ten different ministries or administrations now manage PAs in mainland China (see Fig 3 for breakdown of agencies managing NRs: more agencies and categories are involved in the territories of Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao but these have not been taken into account in the present review.

A few very large NRs in sparsely-populated areas of Tibet, Xinjiang and Qinghai account for about 30% of this coverage, and the coverage in other provinces is significantly lower (see Fig 1). Protected area coverage in the eight westernmost provinces is around 20%, and in the rest of China the coverage is barely 5%. So the coverage is far from even over the country. The NR legislation is very restrictive with respect to human activities in all of the three management zones provided for, but many NRs are simply superimposed upon a mosaic of land uses that are often in severe conflict with the legislation. There are too few data to allow a reliable breakdown of the 15% coverage into an accurate reflection of the level of protection provided on the ground.

2.2 Legislative framework

There are several regulations on PAs: the Nature Reserve Regulations, the Temporary Regulations for Scenic Landscape and Historical Site, and a Management Measures for Forest Parks (See paper of "A Review on Management System of China's Nature Reserves" in the book of China's Protected Area). All NRs are established under the 1994 Regulations of the People's Republic of China on Nature Reserves which allow for only one management category, but NRs are established for a variety of purposes and at different levels of government (national and local (provincial. prefectural, county)). NRs are assigned to one of three major types – wildlife protection, ecosystem protection or natural monument protection, although most reserves include elements of more than one type. Table 2 shows the numbers of NRs in each of the major types.

Current legislation has been found to be inflexible and ill-matched to the real situation of most PAs in China, so various teams are already engaged under the National People's Congress Environmental Protection and Nature Resources Conservation Committee in preparation of a new law for NRs, and revision of existing regulations for SLHSs.

The three management zones available are the core area with no use, habitation or interference permitted, apart from limited scientific research; buffer zone where some collection, measurements, management and scientific research is permitted (but which is not really a buffer zone in the usual international meaning of that term); and experimental zone where scientific investigation, public education, tourism and raising of rare and endangered wild species are permitted. There may also be an outer protection zone (which is a buffer zone in the usual international meaning of the term) where the normal range of human activity is allowed with restrictions if those activities have damaging effects inside the NR.

Local governments coordinate between government agencies, and control regular investments, operating budgets and salaries of staff in many PAs.

2.3 Gaps in protected area coverage

Evaluation of the coverage and effectiveness of the NRs of China with respect to ecosystems and species was undertaken by the task force using a GIS-based analysis approach. Note that scenic sites and forest parks were not included in this analysis because it was too hard to obtain the requisite data. Boundaries of all NRs were digitised into an ArcInfo GIS system. Some small reserves were entered as points due to lack of boundary data. This coverage was then overlaid and analysed against a classification of the country based on 124 recognised biogeographical units and the distributions of all 3,254 vertebrate species (not including marine fish). The full analysis is attached as Paper of "GAP analysis of NR system of China" in the book of China's Protected Area. Some of the main findings are given in this section.

The GIS analysis identified certain areas (including Tianshan, Jinji Mts., Eastern border of Qinghai Province, Southeast Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, Huangtu Plateau and Northern Guangxi) as relatively underrepresented in the national coverage. The analysis also identified gaps in the ecosystem coverage, with some biogeographical units having no PA coverage or only minimal coverage, some biodiversity important biogeographical units are under protected and many threatened species are also not covered, or not covered well, by the NR system. Considering for the moment all species of mammals (560), reptiles (391) and amphibians (287), 48 species are not covered by any NR and it is estimated that there would be much more plants are not protected at all. Relatively few marine NRs have been established and there are none NR along the coasts of Southern Shandong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces to protect wildlife living in sea.

In conclusion, the current PA system does not fully represent the feature of China's biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Furthermore, individual PAs are not connected well by habitat corridors.

Figure 1: NRs in China

Figure 2: Numbers and areas of NRs each year in China

Figure 3: Distribution of NRs by number among different agencies

SFA: State Forestry Administration; MOA: Ministry of Agriculture; MWC: Ministry of Water Conservation; MOC: Ministry of Construction; MOGM: Ministry of Geology and Mineral Resources; MLR: Ministry of Land Resources; SOA: State Oceanic Administration; SEPA: State Environmental Protection Administration.

Table 2The Types of NRs in China (Department of Natural and Ecological Conservation, SEPA, 2002)

|

Type |

Number by the end of 2001 |

Area by the end of 2001 (1000 ha.) |

|

|

| |

|

Forest ecosystem |

769 |

224.5 |

|

Prairie and meadow ecosystem |

33 |

35.1 |

|

Desert ecosystem |

20 |

362.4 |

|

Inland wetland and watershed ecosystem |

137 |

216.1 |

|

Ocean and coast ecosystem |

40 |

10.1 |

|

|

| |

|

Wild animals |

325 |

415.0 |

|

Wild plants |

111 |

21.3 |

|

Natural Monuments? |

|

|

|

Geological Formations |

90 |

11.0 |

|

Paleeontological |

26 |

3.6 |

|

1551 |

1,299.1 |

2.4 Protected areas in the wider development context

The PA system is not directly connected with the government plans for overall land use and development programs at national, provincial and county levels. So large development projects often take precedence over the interests of PAs. However, China's new "Scientific Development Perspective" calls for a higher level of recognition for PAs.

A new approach to PAs is being put into practice by SEPA through the planned Ecological Function Conservation Areas (EFCAs), large areas that include settlements and a wide range of human activities by design and often overlie existing NRs. The aim is to provide coherent guidance to land use across certain critical ecological zones with important biodiversity and ecological processes.

2.5 Funding mechanisms

In total and conservatively estimated, the economic value of the combined functions of PAs in China is equivalent to and linked with more than 30% of national GDP.

Protected areas are funded by a variety of mechanisms. National Nature Reserves may receive funding from ministries for infrastructure construction, while salaries may be paid by provincial budget and, in many cases, by county budget. Provincial Reserves receive much less funding from the government except infrequent allocation under specific projects, and salaries and operation are usually funded under the government at province, prefecture or county level. Establishment of most PAs is based on the willingness of county governments, and economic arguments are essential to persuade them of the value of setting aside resources for PA management.

In practice the bulk of PA funding comes from provincial and county sources. For instance, until 1999 Yunnan province had spent a total of 58 million RMB on construction of PAs. Some provinces are much weaker in this capacity than others. It is often the economically poor provinces and counties that contain the best natural areas for biodiversity.

The national government annually allocates 30 million RMB to national NRs. These funds are mostly expended on infrastructure development. About 30 reserves can get the fund each year to among the total of national NRs now standing at 226.

3. Problems with the Current System

The Government of China has recognized the benefits provided by PAs and has legally protected over 4000 sites (see Section 1) and put in place extensive environmental legislation. However, despite the measures taken, the integrity of many PAs, and the effectiveness of PAs in providing national, regional and local benefits is still at risk from pressures of human population growth and economic development.

Road building, mining, oil exploration and extraction, pipeline construction, dams and water diversions and other large infrastructure projects are all essential components of economic development but they can have devastating effects on natural ecosystems if not planned carefully, and there are many examples of such developments affecting PAs.

Over-harvesting (or harvesting in ways that damage the ecosystem) of wild animals, trees and other plants, and overgrazing also pose threats to PAs, as do drainage and conversion of wetlands for agriculture and aquaculture, pollution from industry, households, agriculture and aquaculture, erosion and siltation, over-use of ground and surface waters, and introductions of certain invasive alien species. Paper of "Problem trees of Pas in China" in the book of China's Protected Area shows examples of problem trees for protected areas.

3.1 Flawed legislative framework

Many of the underlying causes of these immediate threats lie in the ease with which activities that provide short term profit at the expense of long term stability can be carried out within the current policy, legislative and regulatory framework. In the rush for economic development ecological systems are being destroyed. Different agencies often pursue their programmes independently without taking into account the full impacts of their actions on PAs, biodiversity, ecological processes or people's lives. Legal ambiguities and straight lawbreaking are responsible for much of this.

3.1.1 Protected areas often do not have control over land use

Protected areas are used as a tool in conservation, but they are often superimposed on a mosaic of different land uses with little or no institutional jurisdiction or influence over the various holders of land-use rights. Under the Chinese constitution all land and sea belongs to the state, but different individuals, organisations or communities may enjoy various powers or rights to make decisions on land use or resource use. Many such tenure rights overlap and often pre-date the boundaries of PAs and this is a source of considerable management limitation and sometimes conflicts of interest between NR management bureaux and local communities.

In some of the less developed ethnic minority areas, community rights are strong and traditional land-uses may have been established although never certified, long before the founding of the PRC. Many farmers have extended the lands that they cultivate beyond their certified limits, but have enjoyed such tenure unhindered for many years. For example, a large part of the Menglun Nature Reserve (part of the well-known Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve in Yunnan) has been abandoned by the Nature Reserve Management in the face of armed demonstration by villagers, and it appears that there may be other parts of the NR that have never legally been under the control of the NR Management Bureau.

3.1.2 Unenforceable regulations

Many NR managers have to tolerate activities inside NRs that threaten species or interfere drastically with ecological function and are incompatible with PA status. The oil fields of Shengli, for example, are fed by large amounts of water pumped out from the Yellow River Delta NNR at the expense of NR objectives. Many NR managers have no control over development activities within the reserve boundaries, even if they are forbidden under the 1994 Nature Reserve Regulations. The boundaries defined for many reserves have created conditions in which laws and regulations are unenforceable. Sometimes whole mines and even towns or cities, are included within NRs, yet none of the available management zones permit this. There is hardly a NR in China where the experimental zone does not contain human settlements, farming, and unsustainable harvesting of resources.

3.1.3 PA Status often no protection against the effects of major infrastructure projects

Many government agencies have influence over land use and development within and around PAs, and they have various missions, all designed for the public good. In practice problems are created for PAs when agencies with overlapping jurisdictions pursue objectives that conflict with the PAs objectives. For example, the policy of construction of a road to every Administrative Village has over-ridden the mission of protection in many PAs, and the policy of reforestation, while apparently beneficial to PAs, may have unintentional effects when it involves planting of exotic species and monocultures inside PAs that should be devoted to diverse natural forest.

Major development projects often have negative impacts upon existing PAs, and powerful government agencies are able to ride roughshod over the legislation with impunity, inflicting damage on PAs and the environment in general. Sometimes values of PAs will over-ride other national policy. But even in cases where projects are considered of strategic national importance, mitigation measures can greatly reduce the impact on the values that PAs are designed to protect. There are of course cases where NR management bureaux prevail over the demands of developers, in imposing mitigation measures for example, but such measures are not always effective. For example, the West to East Pipeline bisected several NRs and provided compensation, and the major highway that will cut through Mengyang NR in Xishuangbanna will be raised off the ground for some sections to allow elephants to pass underneath, the Golmud-Lhasa railroad was designed to allow Tibetan Antelope to continue their migration between two PAs, and a railway scheduled to be built inside the Cao Hai NR was resited elsewhere. But these are exceptions: the general pattern is for large infrastructure projects to go ahead regardless of PAs, as in recent approval for a dam project that will affect Mugecuo Lake (part of the Gongga Shan Scenic Area) in Sichuan. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is often used merely to design mitigation measures, and not as a tool to decide whether or not to carry out the particular development.

Existing regulations allow for the de-gazettement or down-grading of NRs. Partly because of this, more powerful agencies can inflict damage on PAs with impunity. For example, in Xinjiang, when the Kalamari Nature Reserve and local government came into conflict over tourism developments inside the NR, the local government was able to arrange to downgrade the reserve to county level status.

3.1.4 Rigid regulations hinder innovative management approaches

The strictness of the current NR legislation is itself a source of problems for managers. It is often necessary to exclude humans in order to protect biodiversity, but by no means always. Some species are actually dependent on certain levels of human activities to create suitable habitat, and these activities include some that are prohibited under current legislation inside NRs in China. For example, migratory geese and cranes rely on cropland for winter feeding in many areas. Yet there are no mechanisms to allow such coexistence under the 1994 Nature Reserve Regulations.

3.2 Funding

The current level of public financing is not sufficient to run the PA system and leads to a variety of, essentially illegal, economic ventures that are in conflict with PA objectives

Although funds are provided by central and provincial governments for PA establishment and management, and the amounts provided annually are increasing, this public funding remains far from adequate, particularly for operational costs. Questionnaires returned from PAs across China indicated major funding shortages for staff salaries and benefits, maintenance and running costs of equipment and infrastructure, travel, compensation for animal damage to surrounding farmlands, legal prosecutions, communications, publicity and meetings with local stake-holders. In short, allocation of state funds for conservation is inadequate, poorly targeted and not well-utilised or transparent.

3.2.1 No stable central budget allocation

PAs in China take more than 15% of the country's land area and play an important role in supporting the ecosystem, a living basis for development. However, the central government has not established a separate account in its budgeting system to support the PA system. This issue has been raised for many years but has still not been properly dealt with. In past years, the government funding to PAs has been significantly increased, but most of them are one time allocation, or on project basis.

3.2.2 Infrastructure takes priority over management

PAs receive major funding only for initial establishment, after which civil servant employees continue to be paid their government salaries but there are zero or minimal funds for management. It is relatively easy for PA directors to get funds for physical construction, but much harder to obtain funding for maintenance and basic operations.

A high proportion of the funds available are spent on the national, high profile sites while most of the sites in the system get almost no funding. There are many PAs with low immediate user values but significant value in terms of ecosystem services and biological preservation that are facing a difficult situation and a funding gap.

Ecosystems are changing, dynamic, and species change their ranging behaviour. Funds for investment in fixed infrastructure are more easily obtained under the current system than funds for operational costs, yet such funds could be wasted if the resources to be protected are no longer in the same place in a few years time.

As many of the current NRs include areas unsuitable for inclusion in strict NRs the infrastructure being provided is not always required, and this represents an additional waste of resources.

3.2.3 Damage to protected area resources from economic ventures designed to raise operational costs

Alternative sources of funding available to the PAs capture only local user values of PAs. Payments for ecosystem services to Chinese society and the services of biological diversity/heritage for China and the global community are not captured by the individual PAs. The net result is a systematic tendency to overexploit user values by means of economic ventures, while ecosystem services and preservation of biological values do not get sufficient attention. PA managers are thus encouraged, or forced against their better judgement, to set up their own sources of funding through various economic ventures.

There are uncertainties with any kind of manipulation of natural ecosystems, and decisions on habitat and species management have to be based on a mix of science and common sense and a clear idea of objectives. However, policies that require NR managers to raise revenue for operational costs have led to activities that are clearly deleterious to the values that the NRs were designed to protect. In Chinese NRs such revenue raising activities include tourism that relies on construction of damaging infrastructure, hotels, zoos and specimen collections, cultivation of food crops, forest, reed and bamboo plantations and fish farming and other types of aquaculture, even though these activities are forbidden within NRs.

Realization of the economic values of NRs is important, but economic activities should be compatible with the objectives of the NRs: assuming that all NRs should provide income through harvesting of resources is misguided. Even when conservation funds are made available as grants or loans to local people for revenue generation, the environmental effects of the activities funded by such schemes are not always well assessed. In some integrated conservation and development projects no environmental criteria are used.

3.3 Management standards

Effectiveness of management has been assessed in three ways: literature reviews of extensive previous surveys, plans and reports; personal observations by Task Force members, and analysis of the results of returned questionnaires sent to PA managers.

3.3.1 Old fashioned management practices

Nature Reserves in China have initiated many questionable practices, such as captive breeding, unnecessary or damaging habitat manipulation, artificial feeding, burning without a fire management plan, predator control, introduction of alien species, and forced relocation of local people. Many of these were standard practices in Europe and N America fifty years ago but were superseded by more ecological approaches. PA staff also miss many opportunities for more effective activities.

Nature Reserve directors are often drawn from professions such as local civil servants: there is no formal career structure with specific PA management qualifications. This may be a contributory factor to some of the interventionist approaches to PA management.

Unsound NR management practices, particularly in taking endangered species from the wild for captive breeding or displays result partly from ignorance of ecological approaches to management, but the underlying reasons also lie in the policy framework that encourages NR leaders to compromise the objectives of the reserves in order to raise money to cover operational costs (see above 3.2.3).

3.3.2 Planning does not reflect potential range of objectives of protected areas

Protected Areas are established under the loose system of types described above in Section 2 and this results in important functions being missed when it comes to developing management plans.

Central planning units, such as the Forest Inventory and Planning Institute, develop Master Plans for PAs. However, these units are short of experts with wide knowledge and experience in conservation and wildlife protection. The existing system of approval of plans is inadequate and does not adequately reflect all relevant stakeholders, lacking an effective supervisory system to monitor performance and use of funds.

3.3.3 Conflicting activities across international borders

In order to take advantage of PA systems in neighbouring countries China has already established coordinating agreements with transboundary reserves in some places, for example with Russian and Mongolia in NE Inner Mongolia, with Russia in NE Heilongjiang and with Nepal in the Himalayas. However, there are conflicts with such efforts demonstrated by Chinese logging companies operating across the borders are destroying possible transboundary reserve areas in Myanmar.

3.3.4 Tourism

Levels of income from tourism at PAs vary greatly, but are generally low. There are some notable exceptions where receipts are high, but very often in those cases the types of entertainment or exhibitions developed to attract visitors are inappropriate for PAs and may be damaging. There is often excessive disturbance to wildlife and other visitors from loudspeakers, fairground amusements and traffic, and too much emphasis on specimen collections and the sale of wildlife or wildlife souvenirs originating within the PA, entertainments such as shooting at live birds (as in Dafeng Milu National NR), and cages with poorly cared for animals, often caught in the PA.

The Task Force recognizes that tourism can provide significant revenue for PAs and a platform for economic development for remote communities living around them. However, tourism and the infrastructure needed to support it can also do serious harm to the environment. Many tourism sites are developed by local government and managed by the Tourism Department. Protected area staff are not appropriately involved during planning stages and find difficulties in controlling impacts. Appropriate guidelines for evaluation and management of tourism are needed.

Tourism in China is more in the form of organized group trips than privately planned tours. Much of the income is collected by the air carriers and big hotels in distant cities, provincial or county tourist departments and tour operators for provision of transport, guides, accommodation and meals, and relatively little may accrue to the PA itself and almost none to the local people whose relinquishment of opportunities for greater economic development has in fact created the conditions for such eco-tourism in the first place.

Such arrangements (a) make it very difficult to convince local people of the economic values of PAs and (b) encourage PA managers to sacrifice long term protection objectives for immediate financial gain and leads to many of the inappropriate developments noted above

3.3.5 Local human pressures

Many PAs face pressures of access to land and resources by poor local communities. Local people often cannot do without certain resources, such as fish, firewood, construction wood, or grazing land that lie within nearby PAs. Domestic stock and dogs wander into PAs and cause damage to wildlife and vegetation. Different types of adjacent or even overlapping land-use may be highly incompatible with the PA management and result in spread of fire, invasive species, pollution or other undesirable factors into the PA. On the other hand, many species of wildlife have ranges that extend beyond the boundaries of PAs and can cause damage to crops or livestock.

Local people living in or near rural PAs are also sometimes restricted in their access to resources. This may be in the local people's long term interests in terms of sustainability of resource use, but many of the benefits from protection of biodiversity and ecological services accrue nationally, regionally, and even globally. So, in many cases, local people are being asked in effect to pay the "opportunity costs" of not using PA resources, and are not compensated sufficiently.

While China as a Party to the CBD has embraced the concept of involvement of local people and fair sharing of benefits from the utilisation of biodiversity, local people are largely excluded in practice and even regarded as a problem rather than an opportunity for collaboration. Local people are rarely involved during the establishment and in management of PAs, and are not encouraged (are sometimes deliberately excluded, indeed) from participation in ecotourism opportunities.

The paper of "At least do no harm: Poverty and Protected Areas in China" in the book of China's Protected Area gives an account of the implications of rural economic development for China's PAs.

4. The Vision - Towards A Modern System of Protected Areas in China

The Task Force recognized the great strides China has made in rationalizing the planning and management of PAs, and in the establishment of a national system of protected areas in terms of numbers of sites, area, completeless of coverage, staffing, budget allocations, studies and projects. The government has a clear commitment to further improve in these areas, and to resolve several remaining threats and problems and has already initiated a review of the NR legislation and begun the preparation of a new NR law (see Section 2 above).

However, despite this great progress the task force sees weaknesses throughout the system ranging from systemic to very specific, and feels that unless these matters are addressed quickly the great investments of land and funds will be largely wasted, biodiversity losses will continue and reductions in ecological and other services provided by PAs, such as climate regulation, watershed protection, erosion control, biodiversity and genetic resources protection and tourism earnings, will cost China many billions of US$ of potential revenue and social benefits.

The Task Force has prepared a number of recommendations for further actions and approaches, supported by technical papers and supplementary documents to this report.

The Task Force's vision is of a PA system fully representative of China's wild species, habitats and ecosystems, including a range of objective based management categories and zones, from strict NRs at one end of the scale and multiple land-use areas with certain conservation related restrictions at the other end. It would be a system that provides a full range of benefits including biodiversity conservation, ecological services, recreation and education and that is valued accordingly. The PAs would be managed by the same over ten agencies as now, but a joint database would summarize the status, size, objectives, management category and zones of each, and uniform standards for reporting the effectiveness of management would be used.

A new, overarching PA law would have established the PA management categories legally, and the NR law currently under preparation and other legislation would have defined in more detail the regime for the various categories of PAs and their associated internal and external management zones. Consideration of PAs would have been fully incorporated into the legislation governing sectors such as agriculture, forestry, water, oceanic, mining, transport, construction and other development, and into revisions of or regulations supporting the current EIA law.

A system plan would have been developed based on accurate data provided by all relevant agencies, that sets targets for representation of species, habitats and regions, provides a wide range of multiple functions, and has coherent links with conservation measures taken outside PAs to maintain connectivity and to mitigate effects within the PAs.

Protected areas would be given full consideration in all regional and river basin development planning as part of the landscape, and a strong alliance of the main development agencies (see Box 2 below for examples of relevant sectors) would be promoting the benefits of PAs on the one hand, and the folly of damaging them through economic development activities that have not been subject to thorough environmental assessment, on the other hand. Such an alliance of line ministries and others, with an interest in the services provided by PAs, would ensure that PA development becomes integrated with and supported by more powerful national programmes through the development of appropriate collaboration and synergies.

Resolution of conflicts between government agencies over activities affecting PAs would be being addressed through establishment of a cross-sectoral mechanism for the multiple functions of PAs to be factored into the development plans. EIA for individual projects would be being carried out rigidly, and there would be a greater emphasis than now on strategic environmental assessment would routinely consider PAs from the start of planning processes for regional development. Laws would be being enforced well and government officials would be being held accountable for lapses in implementing environmental legislation.

All PA management would be following management plans approved by higher authorities, and would take fully into account the people living within and around the boundaries. Supervisory bodies at provincial level would be evaluating plans and results. Special attention would be given to the plight of local people whose relinquishment of the use of PA land or other resources has led to poverty or other difficulties, and it would be mandatory to take into account local people in all management decisions that have an effect on their livelihoods.

The system would be funded through innovative public funding mechanisms that allow payments for ecological and other services realized at various distances from the PAs – at the global, national, regional and local levels, as well as through direct cash income such as from concessions to tour operators.

A professional career structure would be in place putting PA management on a par with forestry or policing as an occupation with its own standards and codes of conduct, with a set of required qualifications defined for each of the established posts, and a system of pre-service and in-service training for personnel (see Box 2 below). Staff would be circulated between regions routinely on postings of various durations. Protected areas would also be given special attention in the training of government officials outside the PA system itself. Capacity would have been strengthened especially in the areas of ecological principles, taxonomy, communication skills, outreach, conflict resolution, grant application, networking with other agencies and other areas not traditionally taught to PA staff.

The public's increased knowledge of PAs and greater involvement in PA management would be creating an easier environment for PA management bureaux to operate in, and there would be much open access to information on development plans affecting PAs.

BOX 2: Sectoral Links Required for an Effective Protected Area System

WATER PAs serve as a vital component of the water catchment, regulation and purification processes ensuring more regular supply of better quality water and flood controls.

ENERGY PAs serve to protect water sources needed for hydropower efficiency and also serve as major carbon sinks in relation to CO2 emission reduction efforts.

AGRICULTURE PAs serve as reservoirs for important wild germplasm of relatives of domestic crops, horticultural varieties and livestock. Buffer zones around PAs are ideal places for in-situ conservation of indigenous varieties of crops being elsewhere abandoned in favour of new high yield varieties. Water supply from PAs is vital for irrigation. Natural pest control and pollination agents dependent on PAs contribute greatly to agricultural productivity.

FISHERIES PAs serve as vital breeding areas and species strongholds for inland, coastal and marine fisheries.

FORESTRY PAs serve as sources of wild seed and germplasm of silvicultural species. They also serve as seed sources for species needed in China's ambitious plans for ecological restoration and combating of desertification.

OCEANIC: PAs protect most important marine biodiversity and has the potential to demonstrate sustainable harvesting and marine resource management

LAND AND RESOURCES: PAs safeguard the most important natural resources and ecological services to support long term interests for livelihoods of people.

HEALTH AND TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE PAs fix hazardous pollutants from air and water. PAs serve as wild sources and buffer zones serve as production areas for the components of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the source of other active compounds of medicinal value or potential.

TOURISM PAs act as important visitor destinations. Although revenues raised at PA gates and facilities are relatively modest as yet, the earnings of airlines, hotels and transport sectors outside the PAs are very large.

CULTURE, CONSTRUCTION, AND EDUCATION. PAs preserve cultural diversity, traditional practices, historic and religious sites and offer educational opportunities.

SCIENCE PAs serve as the natural laboratories for research and experimentation for the development of biological discovery and understanding.

LAW ENFORCEMENT In reflection of the great value of public services derived from PAs, law enforcement agencies and judges must be alerted to pay greater attention to enforcing PA regulations.

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS. PAs provide benefits to local communities, the wider public, including civil society organizations, and the private sector and should also seek to draw these into the broader constituency of support.

5. Recommendations

5.1. Establish a comprehensive legal framework for an advanced system of protected areas based on the full range of protected area objectives

The Task Force is convinced that new legislation and a wider range of PA categories is required, and has discussed extensively the advantages and disadvantages of various approaches to formulation of new laws and revision of existing ones. The new legislation could be comprehensive, including the detailed regulations for each type of protected area, or it could be of a framework or umbrella type providing reference to specific subsidiary regulations to be published by relevant management authorities. The former approach gives greater legal power to the regulations but the latter approach provides greater flexibility to adapt regulations to specific local conditions and opportunity for periodic revision without having to reformulate the law itself.

Three main options were discussed:

Option 1: Separate laws for each type of PA

Option 2: Extension of the ongoing work of drafting a NR law to include other/new types of PA

Option 3: A broad framework 'Protected Area Law' under which would fall the more specific legislation (including the ongoing work on NR law)

Option 3 is recommended by the Task Force and specific recommendations with regard to legislation and safeguards are summarized below. Full details are given in Paper of "Proposals for Development of a Protected Area Law" and "Applying the Protected Area Category System in China" in the book of China's Protected Area.

5.1.1 General recommendations on legislative framework and categories

1. Ensure that the preparation of the current NR law under the auspices of the National People's Congress follows the principles laid down in the following specific recommendations for a framework PA law

2. Resolve legal issues of property and customary rights of local communities on land and natural resources

3. Establish clear objectives of management for each PA type, using a range of PA categories to meet diverse management objectives, from the strictly protected to the sustainably used areas. For this purpose, the 1994 IUCN guidelines on PAs management categories may be consulted to build upon and improve the existing Chinese categories of PAs.

4. The law should establish the responsibilities of different PA management agencies – and should cover funding mechanisms, procedures for submission and approval of plans, supervisory and control mechanisms, requirements for standardization of reporting, monitoring and information sharing, and capacity development and career structure for PA staff.

5. The law will resolve the problems of conflicting jurisdictions and allow PA managers adequate decision making rights or representation on local decision making bodies

6. Establish the requirement for each PA in every category to have clearly stated objectives from the date of gazettement and for those objectives to form the basis for management planning and internal zoning

7. Include the revised PAs categories system within a comprehensive framework law on PAs.

8. For each protected area, prepare detailed implementation regulations to achieve the agreed management objectives and define the activities permitted or prohibited in different management zones (where necessary and appropriate) so that specific functions, including scientific research, can be performed.

9. The implementation regulations should consider resources used by local communities, permitting sustainable subsistence use where this is consistent with the particular category of PA and its management objectives.

10. Introduce a legal provision for the establishment of community managed PAs corresponding to the appropriate management categories.

11. When PAs are divided into different management zones, provide for areas to enable community use of resources, where suitable and consistent with the management objectives.

12. Strictly guard against revenue generating ventures that conflict with the management objectives agreed for the particular category of protected area.

13. Develop and use the full range of PA categories to enable conservation planning to be conducted at the landscape/bioregional scale, within the overall planning frameworks of provincial, county and municipal governments, and within an overall national PA system plan.

14. Assess all PAs against the revised categories system to review their management objectives and assign them to appropriate categories based on the local context and established objectives. However, in doing so, guard against expediency oriented dilution of protection status.

15. Implement a broad communications and awareness raising strategy to promote the use of the generic term "protected areas" to encompass diverse types of areas, and enhance understanding of management objective-based categorisation of protected areas.

16. Successful implementation of the recommendations in this report will rely on more than a single law: revisions of other relevant laws will be required so that they incorporate PA considerations, and new laws currently in preparation, such as the Yellow River Law must include PA considerations from the beginning. It is recommended that a review is made immediately of the legislative changes that should be made to enable a new PA framework law to function without conflict and ambiguity.

17. Detailed discussion and justification about the management objective-based categorisation of PAs in China is contained in Paper of "Applying the IUCN Category System in China" in the book of China's Protected Area. The recommended categories are listed in Table 3.

Table 3: Recommended Categories for China's Protected Area System

|

Category |

Name of each category |

Objectives |

Examples |

Existing protected area types in China |

|

Ia |

Strict Nature Reserve |

To preserve habitats, ecosystems and species in as undisturbed a state as possible to maintain genetic resources in a dynamic and evolutionary state, and maintain ecological processes. To permit non-destructive scientific research. |

Dinghushan, Foping, Wolong, Xishuangbanna, Nanji Islands, Changbaishan |

National NRs of forest ecosystem type, including the core zone |

|

Ib |

Wilderness Protection Area |

To preserve the natural attributes and qualities of a large area of unmodified or slightly modified land/and or sea, without permanent or significant habitation. To enable local resident people living at low densities and in balance with the available resources to maintain their lifestyles. |

Qiangtang, Kekexili, Anxi Jihan Desert, Wula'ersuosuolin, Menggu Wild Ass |

National NRs of parairie and meadow ecosystem or desert ecosystem, including the buffer zone |

|

II |

National/provincial park |

To protect natural and scenic areas of national or international significance for spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational or tourism purposes. To take into account the needs of the resident local people without adversely affecting the other objectives of management. |

Juzhaigou, Huanglong, Fanjingshan, Jinyunshan, Jinfoshan, Gonggashan, Xiguliangshan, Danxiashan, Qinghaihu, Zhumulangmafeng, Yaluzangbu Gorge, Taibaishan, Hanasi, Lushan |

NRs of the ecosystem, wildlife or natural monument types, including the experimental zone; National SLHSs or Forest parks |

|

III |

Natural monument |

To protect specific outstanding or unique natural features for their inherent rarity, representative or aesthetic or cultural significance. To provide opportunities for research, education, interpretation and public appreciation. To deliver such benefits to local people as are consistent with the other objectives of management, and ensure that such use is sustainable. |

Jixianshangyuan, Dianzixiang, Yitong Volcanos, Shanwang biological fossil, Heyuan dinosaur egg fossil, Wudalianchi, Qinglongshan |

NRs of the natural monument type |

|

IV |

Wildlife Sanctuary |

To maintain the habitat conditions necessary to protect species, biotic communities or physical features of the environment through specific manipulative management intervention. To deliver such benefits to local people as are consistent with the other objectives of management, and ensure that such use is sustainable. |

Datian, Dafeng Milu, Wanglang, Zhuhuan |

NRs of the forest ecosystem, wildlife type |

|

V |

Protected Landscape/Seascape |

To maintain the harmonious interaction of people and nature through the protection of landscape/ seascape and the continuation of traditional landuses and cultural practices. To maintain the diversity of landscape/ seascape and habitat, and of associated species and ecosystems. To benefit local communities through the sustainable use of the PA resources and services. |

Many current forest parks and ecological function areas. Many "outer zones" of current nature reserves, Xiangshan |

NRs of the forest ecosystem type, parairie and meadow ecosystem type, including the outer protection area; SLHSs; Forest parks, Coastal parks, Wetland parks, Community PAs |

|

VI |

Ecological Reserve/ Managed Resource Area |

To manage largely unmodified natural systems to ensure long-term protection and maintenance of biodiversity and ecological function, while providing a sustainable flow of goods and services to meet community needs. |

Panda corridors, Dongzaigang, Xingkaihu, Ruo'ergai, Poyanghu |

NRs of all kinds of ecosystem types, including the experimental zone; Forest Park, Coastal parks, Wetland parks, Community PAs |

5.1.2 Recommendations applying specifically to safeguards

Under the new EIA Law of China (and under a future PA Law), detailed regulatory controls could be developed to control PA management and to effectively safeguard PAs from development projects (see Boxes 4 and 5 below). However, supporting these safeguards requires technical guidance and supervision of projects that affect PAs. Projects may be outside and even quite far away and still have major impacts on the PA. Since poor implementation of good laws has been a chronic problem in this sector, capacity building and improved enforcement will also be required.

1. Fully independent evaluation of proposals for initial establishment of PAs, and subsequent PA Master Plans, Management (Operation) Plans and their implementation, with attention on results. Audits of performance of PAs should be based on published indicators and standards, for example, IUCN is now drafting the "Use of the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories in regional criteria and indicator processes for sustainable forest management".

BOX 4 Recommended Criteria for Approval of Development/Operational Funds for PAs

Preparation of management plan containing:

2. The application of EIA requires further development to provide the basis for strategic environmental assessment. Protected areas should be given central consideration in the ongoing development of regulations.

3. Plans for any infrastructure development that might impact PAs should always be subject to full EIA at the earliest planning stage (as now required by law). This includes projects distant from the PA itself, such as downstream hydro-projects that raise water levels to inundate areas inside the PA, or that cause people to resettle into PAs or adjacent to PAs. PAs should be fully considered in Strategic EIA and regional plans.

4. After development plans are approved, independent supervision of these projects would ensure that mitigation measures are carried out, that funds are used as intended, and that there is no unanticipated environmental damage.

5. Improve supervision of the EIA process in PAs by the appropriate government offices under SEPA.

6. Incorporate requirement of EIA into the PA Law. Any construction project in a NR or other strict PA should be required to undergo an EIA, this should be so even if the project is designed by the NR with the objective of improving protection, such as tourism development, reintroduction programmes, or fire-breaks. Alternative designs and mitigation measures should be considered, along with the no action alternative.

7. Do not allow PAs to retain gate fees, and income derived from tourism services (sales, meals, accommodation etc) but set the system such that concessions are offered to local communities to provide ecotourism services with the PAs retaining firm control over developments (even those being pushed by local government) to ensure that they are in line with the PA management objectives.

5.2 Design a new and comprehensive protected area system and build a multisectoral alliance to support it.

The Task Force recommends that China improves its PA system. When designating new PAs and corridors, and changing in status, category, zoning or boundaries of existing ones, it is necessary to make a link to land cover, land-use, future development plans, financial feasibility and involvement of local governments at various levels. Such a PA system plan should be integrated into the overall development plan at national, provincial and county levels. This will save resources, ease management problems and inconsistencies, clarify land tenure disputes and maximise benefits of PAs.

The specific recommendations are as follows:

5.2.1 Establish and support a comprehensive Gap Analysis on the current protected area system.

This will assess not only what species or ecosystems are covered, but also what ecological services are provided, and the values of PAs for other uses such as research, education, tourism, as well as long-term viability in the face of anticipated future developments and climate change and the degree of connectivity needed by the ecosystems and species for which they are established. To complete this task, it is necessary to extend gap analysis studies with particular reference to ensuring that altitude is considered as well as two-dimensional coverage. All types of currently established PAs will be covered in the analysis, including forest parks, scenic areas and non-hunting areas as well as NRs.

5.2.2 Develop a system plan of a PA network in a more strategic and systematic manner.

This includes designating new PAs and changes in status, category, zoning or boundaries of existing ones. It should also include corridors (management criteria for key landscape) with reference to land cover, land-use, future development plans and involvement of local governments at various levels.

5.2.3 Integrate the PA system plan into the governmental "Five Year Plans" at national, provincial and county levels.

With such an integration, the needs of PAs will be mainstreamed hopefully with necessary budgetary and administrative support

5.2.4 Form a higher-level and cross sectoral alliance to ensure the integration of PA and overall land use and development planning; coordination among line ministries and supervision of PA effectiveness.

This alliance may follow the model of former Environment Committee under the State Council (dismissed in 1998) with appropriate adjustment. The need of a similar committee also appeared in recommendations made by other CCICED task forces. So the joint suggestion might be achieved by multiple task forces to form a National Environment and Resources Committee under the State Council. Under which, sub-committees could be set up to oversee different themes such as PAs, water and watersheds and energy. The terms of reference of the PA sub-committee would be:

1. Develop overall and dynamic strategy and legislation of PA in line with overall sustainable development context and national conservation priorities

2. Coordination among line ministries and bureaus

3. Rights for approval / rejection of development programs with direct or indirect effects on PAs

4. Coordination with development authorities for balanced resolutions when facing conflicting agendas

5. Establishing criteria and processes for evaluating PA management plans and implementation

6. A platform of effective and regular information exchange and feedback top down and bottom up, and horizontal to 1) support wise decisions by PA authorities; 2) raise the awareness and understanding to the importance of PAs among higher decision making agencies, governments and the public

7. Build in accountability to the public on implementation of laws and regulations by management authorities

The committee should:

1. Be affiliated to SEPA, with the condition that SEPA withdraws its involvement in direct management of specific PAs to avoid conflict interests

2. Reflect high authority, expertise and civil participation among its members, including:

1) At least one senior official above ministerial level

2) Relevant ministries' representatives at DG level or above, namely:

3. Experts in natural and social sciences, legislation,economics and management

4. Civil Society Organization (CSO) representatives

5. Community representatives

5.3 Ensure that people benefit, and do not suffer, from living near to protected areas

Most areas valuable for biodiversity are found in remote regions where poverty remains an important issue. Therefore, in establishing and managing PAs, we must recognize many relationships between resource management and the needs of rural people. All decisions taken by PA managers must consider the socio-economic context of the PA, and PA management plans should be prepared on the basis of consultation with stakeholders, giving particular attention to income sources for local people. A proportion of the income earned by the protected area, for example through gate fees, should be paid to local communities in return for managing their land in ways consistent with the protected area. (See Paper of At Least Do No Harm – Poverty and Protected Areas in China" in the book of China's Protected Area)

The role of PAs in poverty alleviation should be treated as circumstances indicate: as said above, there is no panacea or universal solution, and PA managers cannot act in isolation from local government. PAs can contribute to poverty reduction in the rural landscape if appropriate policies and management measures are put in place. Satisfying local pressure by allowing access to PA resources is rarely a satisfactory or sustainable option. PA management can help local communities through employment, involvement in ecotourism sector, etc., but this is a clear case where the broader alliance must be called upon and resources from other sectors and programmes must be brought to bear in helping to solve poverty issues in such priority areas (see Paper of "Adjacent Area Management Planning in Practice" in the book of China's Protected Area)

An increasing number of PAs in China are involved with various activities designed to alleviate poverty and develop the local economy, and these often involve measures to allow controlled use of natural resources from the PA. Addressing poverty through generating more income from natural resources in such areas may result in unsustainable pressure on the natural resources the PA is designed to conserve. Wise choices are needed to ensure that conservation and development are partners instead of competitors for limited resources.

It is recommended that all planning of rural poverty alleviation programmes should also consider their impacts to PAs. For example, promoting goat herding among rural farmers living around PAs can unintentionally subvert efforts to restore forest inside PAs, and fish farming enterprises can lead to introduction of exotic species and eutrophication as well as overharvesting of food species.